Tallinn Art Hall as a testing ground for the public sphere of the transition era: The cases of Group T and George Steinmann

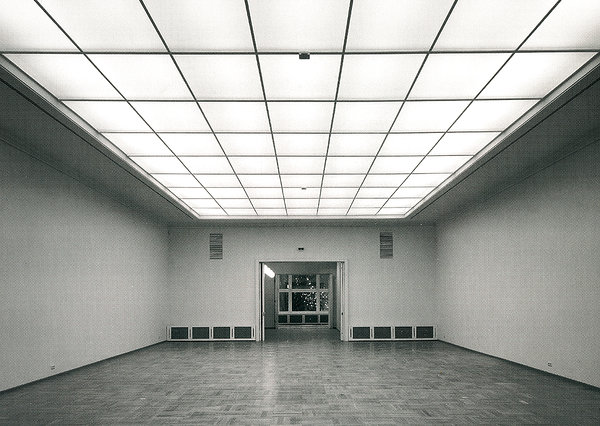

Photo: Museum of Estonian Architecture

With the launch of perestroika and glasnost in the second half of the 1980s, and the following reindependence process of Estonia, a democratic public sphere was actively being ‘in the making’ by the first years of the 1990s. Like all cultural institutions, art spaces were also contributing to the process. The current article is focused on Tallinn Art Hall as the most important and representative premises for contemporary art, aiming at an insight into the different ways how this institution participated in the processes of constructing a developing democratic public sphere. The case in exemplified by two consecutive but inherently contradictory art events, both addressing Tallinn Art Hall as a physical and discursive space but rethinking the space in very different terms, employing vastly different artistic strategies to assert their, and the Art Hall’s, position as agents in the public sphere. The first act takes place in the years 1991 – 1993 when during a couple of performance art events Group T transformed the premises of the Art Hall into a venue of a continuous performance, generating a counter-public sphere by creating a possibility of community without community. The second act follows, overlappingly, in 1992–1995, when George Steinmann envisaged a full renovation of the Art Hall as a piece of sustainable mind-sculpture, intervening with a participatory practice building up an international network across the realms of art, politics, and finance.

Tallinn Art Hall is a building and an institution with a notable history, having been erected in 1934 as a result of an architectural competition by Anton Soans and Edgar Johan Kuusik. Modeled on German Kunsthalle typology, it consists of non-profit gallery spaces and artists’ studios upstairs. Its location as one of the defining structures of the main urban square and its modern functionalist aesthetics underlined both the importance of art in society as well as the progressiveness and forward-looking nature of its activities. During the Soviet years, the institution was run by the Soviet Estonian Artists’ Union, continuing to function as the prime official exhibition space. But bad upkeep and lack of funds left the spaces more and more dilapidated over the years, and by the end of the 1980s it was far from its original pristine impression with worn floors, electricity problems, rotting windowsills here and there, and poorly kept communal and sanitary spaces. The Art Hall’s physical conditions together with its multiple layers of symbolic meaning invited different art projects to manifest themselves in dialogue of the spaces. How did these site-specific art events contribute to the institution’s functioning as a public space, how did it resonate with the concurrent social developments, and what kind of public was constructed, temporarily or in a more permanent way, through them?

Group T’s A Guide to Intronomadism and Eleonora:

a continuous performance creating a community without community

‘A performance is an event where nothing takes place, and once it is over there will be no memories of it.’[1] Such was a manifestation by Hasso Krull, a member of Group T, on the occasion of a performance week ‘Eleonora’ that took place at the Tallinn Art Hall in February 1993. The statement of Krull, a philosopher, writer, and then the main ideologue of Group T, was issued in the hope of transcending the common urge to decode a ‘meaning’ of performance, and focus on the event as pure presence instead. And it was exactly the presence of Group T’s performative actions – a different, hitherto unseen way of occupying an exhibition space – that temporarily transformed the Tallinn Art Hall, proposing a new way of being-together in an institutional space. By doing that, Group T helped a specific counter-public to emerge and temporarily constructed an alternative public sphere.

The performances at the Art Hall – an exhibition A Guide to Intronomadism that took place Feb 20th– March 10th, 1991, and a performance week Eleonoraon Feb 15th – 21st, 1993 – may be seen as the culmination of Group T’s activities in Estonia. Group T, initiated by architects Raoul Kurvitz and Urmas Muru in 1985 as a loose collective of creative individuals involving also painters, musicians, writers, actors, and philosophers, had evolved from the initial production of paintings and spatial installations increasingly towards non-object-based art, focusing on multidisciplinary performances that they themselves described as rituals[2] and that have been mainly characterised as brutal[3], maneristically contradictory[4], and self- aggressive[5]. To be exact, with the event of A Guide to Intronomadism exhibition they proclaimed their activities to be finished, as if the ‘conquering’ of the local most important art venue had served as a climax and self-fulfillment; with Eleonora two years later they were actually only acting as curators with the most part of the performers being their invited guests from the Baltics, Scandinavian countries, and Estonia.

A Guide to Intronomadism had some artworks permanently on display like Peeter Pere’s paintings, a couple of video works by Urmas Muru and Tarvo Hanno Varres, Raoul Kurvitz’s installations and Tarvo Hanno Varres’s photo series, but the main programme consisted of performances that took place every night (except Tuesday when the gallery was closed) for the two weeks in a row. By no means were these spontaneous happenings – there was a preconceived programme with about half of the performances accompanied by specially composed or sampled music by Ariel Lagle or Raul Saaremets and Allan Hmelnitski, and all the pieces had exact titles, many of them more or less referencing to various inspirations from history or pop culture. Whereas Group T was known for accompanying their endeavours with manifestoes from their very first one in 1986, this exhibition was preceded by a programmatic article[6] in weekly Eesti Ekspress, written by Hasso Krull who was at the time the main introducer of continental poststructuralist philosophy and literary theory in Estonia. Thus the main inspiration for the article as well as for the title of the exhibition was Gilles Deleuze’s and Felix Guattari’s Nomadology. Krull references their understanding of intensities of movement, combining the dynamics of mind-boggling racing and complete stillness – evoking such moments of intensity would be the main aim of an art event instead of some kind of expression of an artist’s self. He also provided the definitive interpretation of the exhibition with an article in the cultural monthly pretentiously ending with a proclamation that the issue of intronomadism never ever requires any more explaning.[7] In it, he bases the actions of Group T on Georges Bataille’s concept of pure expenditure, as a way to step out of any natural chains of causality, resisting the system of production and consumption, and defying the need to create value. This is achieved by anti-creativity, destruction, bodilyness, and spectacularity.

Eleonorawas again announced by a manifestative article Nomadism repeated by Hasso Krull, referring to a comeback or recurrence of previous experiences at the same place.[8] In a playful manner, Krull proposes three possibilities of nomads’ identity: they may be gods, once departed from the humans’ realm because of boredom; they could be escaped criminals; or happenstance creatures who are epicine, immortal, and alien-like – anything outside normal implying that any interpretations of their actions conforming to regular social norms and expectations would be inappropriate. The event was named with a female name Eleonora also in an attempt to annul any reference to meaning. For three nights from Friday to Sunday, there were performances by Siim-Tanel Annus, Maria Avdjushko, Lauris Bruvelis, Ansis Egle, Valts Kleins, Hasso Krull, Raoul Kurvitz, Ariel Lagle, Urmas Muru, Irma Optimisti, Kirsi Peltomäki, Peeter Pere, Rühm T, Kimmo Schroderus, Jaan Toomik, Roi Vaara, Tarvo Hanno Varres, Nalle Virolainen, Ugis Witins, Piotr Wyrzykowski, Vilnis Zabers and others.

Compared to the conventional exhibition practice, what was new with Group T’s activitites at the Art Hall was the redefinition of the venue as an eventspace, as a setting for continuous practice instead of a place for exhibiting the end results of some previously completed processes. The traditional concept of an exhibition was reworked into something that is in constant flux, continuously changing, and that of course lays new and more ambitious demands to the authors as well as to the spectators, who by becoming a part of this constant reworking of the space and its contents, inevitably lose their safe role as witnesses but will be transformed into participants instead. As Heie Treier remarked in a contemporary review, the way the exhibition was changing on a day-to-day basis, was binding the artists strongly together with their works, naturally requiring extra effort to adjust the setting and create new input daily.[9] In compliance with postmodern pathos, it naturally contributed to the overall message of eradicating stable structures and of impossibility of meanings – the absence of content behind the form was suitably compared to Oscar Wilde’s The Sphinx Without a Secret.[10] The experience of the art event consisting of a series of sub-events unfolding over a period of two weeks time highlights the temporal, virtual aspect of it, a heightened sense of being in the moment, of participation, and by virtue of the latter, a formation of a temporary community. The setting, in the sense of the institutional space and even in the form of exhibition situation as a kind of stage, is just a prerequisite. This has been literally confirmed by Urmas Muru: “A gallery space is just an address, nothing else. … It is just like with the club scene – the club space itself is nothing, it is an address, a location. Everything depends on who is playing the music, this is what defines the essence of the party.”[11]

This desacralizing of the institutional exhibition space – the devaluing of a physical space in itself, for that matter – has definitely to do with Group T’s main protagonists’ background in architecture that gave them a heightened awareness of how any given space works together with the art that takes place there. Their deconstructivism-informed architectural practice that Urmas Muru, Peeter Pere, and to a lesser extent also Raoul Kurvitz pursued in parallel to their trailblazing career as performance artists could be easily described in Bernard Tschumi’s terms of ‘architecture and event’. As Tschumi has famously stated, there is no space without event, no architecture without a programme.[12] Architecture could not be dissociated from the events that ‘happened’ in there. Event, particularly political event, has the capacity of disrupting simple casual relationships between form and function, allowing the possibility that anywhere could be used for anything, at any time. This position opened up a political potential of using the particular, historical and highly symbolically loaded space of Tallinn Art Hall in a subversive way, creating a counter-public space critical of mainstream social processes of the time. ‘It was a pure laboratory, and we took everything it was possible to take of the Art Hall,’ as they themselves have remarked.[13]

Group T’s conception of an individual’s relationship to the society was also strongly influenced by Georges Bataille, and the latter’s understanding of architecture’s role in society as something like a mirror stage in the development of an individual and architecture as a society’s superego lead to the imperative of dismantling architecture.[14] In this vein, Group T’s performances were deliberately destructive not only towards their own bodies but also towards the space that contained the events. In the spatial hierarchy of the Art Hall, the main hall held the highest importance with indirect yet even and luminous light emanating from the glass ceiling, the light being the most important feature of the room that let the artworks being displayed to their best. As the first move in desacralising the space and the art event, Group T covered the glass ceiling with black tar paper, darkening the room for the whole duration of A Guide to Intronomadism. Furthermore, for the performance Death of Marat they removed the glass panels for a body of a performer to be hung down from there. Another valuable feature of the Art Hall spaces was the floor – during the Soviet times, under the conditions of general bleakness of public spaces, the existence of a pre-war wooden parquet, just like any fine architectural detailing from the period, had begun to work as a reference towards the dearly held pre-Soviet independence era. This floor, already suffering from bad maintenance, got worn even more with Urmas Muru’s installation The Carpet burying the parquet underneath granite gritstone. The situation wasn’t made easier with Raoul Kurvitz’s performance Myra F involving skiing on the floor, and Raoul Kurvitz and Maria Avdyushko litting a fire on it for Wolf and Seven Little Goats; the same happened with Andanteby Urmas Muru and Eve Kask. Those primary elements of earth and fire were complemented with water, pouring down from the smashed buckets in the performance Death of Marat. The opening performance of A Guide to Intronomadism involved drilling holes, not quite into the building itself but into large cardboard boxes that may be interpreted as some kind of primary architectural units. Still, the structure of the Art Hall did not survive quite unhurt – while preparing for the performance of Piotr Wyrzykowski during the Eleonora week, an accidental pickaxe hole was made into its wall. As a whole, this testifies of quite a nihilistic relationship to the building and a conscious decision of ‘making the place their own’ – as Urmas Muru has recalled, the venue did not have any security measures and they were free to inhabit the place on a 24 hour basis if the preparations required.[15]The Art Hall was truly made into a production workshop instead of a venue for displaying high art, the connotation of production processes being accentuated by the choice of materials – tar paper, rough metal and rust, gritstone, industrial prefabricated details, plastic etc. The contrast was deliberate and acknowledged: ‘At the will of the rioting artists, the attributes of an industrial modernism, destined to doom, were displayed right in the middle of the noblest temples of art which were, in the course of the most blasphemous orgies, rudely subjugated without any resistance.’[16] In this sense, the performance weeks at the Art Hall emerge as a culmination of a series of attempts at dismantling and subverting the spaces most intensely loaded with symbolic meaning in the Estonian culture, starting with the museums of national writer Tammsaare and artist Adamason-Eric, also revered for his reinterpretation of national heritage, continuing to the Song Festival Grounds, and the infamous Black ceiling hall of the Writers’ House.

Whereas the ritualistic aspect of the Group T’s performances has so far mainly received interpretation from the aspect of the performers as postmodern pseudo-shamans or demiurges[17], an equally important effect of any rite is a building up of a (temporary) congregation of participants. The issue of participation was crucially acknowledged from the start. Already in the very first interview with Raoul Kurvitz and Urmas Muru on the subject of Group T it was declared that the meaning of group comes entirely from its public.[18] Elsewhere, they have stated that their identity is based on a certain common ‘generational feeling’[19], and over the course of years the membership of the group has been in considerable flux, consisting initially of the three core architect members together with painters and painting students Tiina Tammetalu, Lilian Mosolainen, Valev Sein, graphic artist Anu Kalm, poet Andres Allan, and musicians Ariel Lagle and Margo Kõlar (the lineup of the second exhibition at the Tammsaare Museum in 1987[20]) but in their later years the painters retreated, being replaced by musicians and actors, with A Guide to Intronomadism already having a long list of temporary collaborators as well.[21] The group has defined itself as an open platform from the start with Kurvitz and Muru proclaiming that anybody interested may become a member of the group and contribute with a performance.[22] This is exactly how Tarvo Hanno Varres recalls becoming a member of the group for A Guide to Intronomadismevent as a young punk, more or less entering from the street as a result of an accidental conversation.[23]But there were also loads of people simply hanging around who were put to good use either in helping out with transport and other similar practicalities, or were used as extras in the ‘mass scenes’ of various performances, receiving more or less exact guidelines for their role in a certain event that left some space for improvisation as well.[24] It was a deliberate choice to call all such ‘groupies’ members of the group, accentuating the constant flux, however the core members retained the position to define the essence and conceptual aims of it. Similarly, it was not really important that the fluctuating members, much less the attending public would thoroughly understand and share the complex theoretical underpinnings of the performances. The blurring of boundaries between the performers and the onlookers was never an intent[25] and the performances followed a preconceived plan however improvisational it might have looked. Nevertheless, the sheer durational aspect of the event unfolding over two weeks created a kind of commonality among the faithful public who cared enough to attend daily. Urmas Muru has recalled that the intensity of the event with performances taking place every night slightly ‘wore out’ the usual crowd of art exhibition openings who were perhaps not used to such an effort.[26] Instead, the evenings were increasingly attended by a new kind of public – the young punks who were daily hanging around at the Vabaduse square and especially in front of café Moskva next door to the Art Hall, and the queer people who were lacking a space of their own in town altogether. Bringing a completely new kind of public to the art institution was acknowledged also in reviews, which appreciated the event’s ability of demolishing a barrier between local art and music scenes, and bringing in new crowds even if it comes with the price of parquet – the Art Hall better be dilapidated but full of people rather than immaculate and empty.[27]

The fusing of the art and music scenes was most effectively completed in Tarvo Hanno Varres’s performance Acid House Dancing Party on March 1st, 1991. It was exactly what the name implied – an acid house dancing party with Raul Saaremets and Allan Hmelnitski playing house music. This counts perhaps as the only event during the whole exhibition which tried to provoke coalescence of performers and viewers, to form a temporary ‘congregation’. As Tarvo Hanno Varres recalls, it was met with surprise and even with dissapointment from the regular ‘art crowd’ who had come expecting a ‘normal’ performance. Many of them left when nothing of such was on offer, to be replaced by the ‘club scene crowd’ who were happy to claim the space.[28] To be exact, in Estonia there did not yet exist a coherent ‘club scene’ at that time, it was more a loose group of acquiantances interested in contemporary house and techno music that was still quite hard to get your hands onto. Also the distinction between punk rock, indie, and techno scenes was fluid and not really established, all these different strands somehow coming together in the form of the band Röövel Ööbik whose frontmen Saaremets and Hmelniski were at the time listed as members of Group T as well, with Tarvo Hanno Varres also starting to play base in the band. The first gatherings with about a dozen interested people playing house music from self-recorded cassettes had taken place in 1990, and there was still half a year to go until an event that may actually be called the first alternative electronic music party at Kodulinna Maja took place in August 1991.[29] Thus, in terms of sound and otherwise, the Acid House Dancing Party must have been as extraordinary for the general public as any other performance of the event.

This attempt at integrating cutting-edge pop culture to the art practice was in no means an isolated occurrence in the practice of Group T. Whereas during the first years of their activities they had intersections with punk, with Raoul Kurvitz, Urmas Muru and Eero Jürgenson staging a performance An Announcement to the Teacher at the Jäneda punk music festival of 1986, and a 1988 performance Discipline by Raoul Kurvitz, Urmas Muru and Velle Kadalipp at the Estonian Industrial Design Office premises being, in the essence, a piece of punk poetry, in the beginning of the 1990s their interests shifted towards more electronic music. They were also increasingly acknowledging the huge importance of imagological choices in building up their public personae[30], and channeling their creative endeavours towards occupying the newly developing media discourse. This may be exemplified by Raoul Kurvitz inititating a series of TV broadcasts Lifestyles– an eight-part series of shows introducing different currents of pop culture, executed with experimental visual language and montage.[31] Due to financial difficulties, the series was broadcast with quite long intervals, starting in 1993 with the first part Camp; continuing with Techno, Feminism (anchored by Viire Valdma instead of Kurvitz), Romanticism, and Intellectuals in 1994; Hippiesin 1995; and Disco and Winners and Losers (anchored by Mari Sobolev) in 1996. The Technobroadcast was clearly the most important to their own creative position at the time, featuring the Manifesto for Technodelic Expressionism that Group T had issued already in 1988.[32] In addition, Technointroduced music from Kraftwerk, Cabaret Voltaire, and Throbbing Gristle, with Raul Saaremets stressing the importance of a total immersion in music and dancing in this all-encompassing sensibility. The visual side featured glimpses from urban design projects by architecture studio Siim ja Kreis, furniture by Toivo Raidmets, glass desgn by Meeli Kõiva, video art of Ene-Liis Semper; and introduced the concept of virtual reality. In voiceover, techno is stated as the part of culture that deals with most radical innovation, something that develops extreme sensual intensity directed towards future; the computer is declared the muse for creative output. At the same time, Urmas Muru began guest editing irregular special spreads called Tsoonin the weekly Eesti Ekspress.[33] These were characterised by an experimental take on graphic design with found graphic source material, psychedelic patterns, irregular layering, use of handwriting, and consciously illegible parts. Content-wise it was a similarly eclectic mix of references and samples on issues like art and technology, French symbolism, narrated dreams, scenarios for possible performances, unexecuted historical and contemporary urban design projects, effects of various narcotic substances, fashion, relationship of art and sex, and senseless samples in fictional languages, all combining into a phantasmagoria of a sophisticated contemporary urban sensibility, as caleidoscopic as the one presented in the Techno broadcast.

The shift from punk towards techno was not a simple issue of the arrival of a new and exciting style of music, rather it was a notable change in mindset and ways of self-assertion under the changing social conditions. While Esto-nian punk has generally been associated with resistance to the Soviet establishment[34], the social position of techno is more ambivalent and greatly in tune with the specific in-betweenness of the transition era. Punk rock’s pretentiousness and grand gestures of negation are replaced by techno’s denial of spectacularity, denial of meaning and truth, and a deliberate lack of message. Techno is seemingly lacking any ideological position, any political aim, and by definition that should also imply a lack on any communitarian ambition. Yet it works as a so-called laboratory of the present[35], generating a certain being-togetherness, an archaic or pseudo-ritualistic commonality and enthusiasm in a shared space. Techno is about complete presence – no ideals are projected towards future, the commonality only opeates in the present. It is a commonality that is formed, unlike the traditional community, around a void instead of a meaningful core – the being-togetherness exists only in the actuality of the dancing bodies without any denominator outside of the event.[36] Each house party reestablishes a commonality, a relationship between the participants without sealing it with clear-cut engagements or being channelled into a political or religious affiliation. Thus it resists everything that closes out the political or that tries to set any rules or boundaries to this totality of being-togetherness. Although seemingly nothing much more than collective effervescence, this festive occasion embodies a change of the state of things, a shaking of the inertia. Its seeming apoliticality turns out to be an essential stratum constituing the social and the political in its claims for a different kind of relationship among people, a different commonality.[37]

The performances of Group T, not only the Acid House Dancing Party but rather the whole two weeks as a continuous ‘party’, may be seen as reestablishing a commonality of bodies each night by creating a temporary alternative community that shares a space and shares, for a specific moment in the present, exactly such ‘collective effervescence’. Jean-Michel Nancy has asked if this characteristic of techno could enable a possibility of being-in-common that precedes any binding principles, to create a commonality before any common denominator.[38] In February of 1991 when the social efforts seemed to be directed to the main aim of reestablishing independence based on historical continuation from the first republic before the Second World War, and commonality was defined in extremely singular, basically nationalistic terms, the question of finding a way for being-in-common defying such simplistic common denominators was urgent. In Group T’s rhetoric, the equivalent to Nancy’s ‘community without community’ is the figure of a nomad – somebody who ‘eradicates their markers of national identity and treats their body as a cosmic spatial entity, as an anti-hierarchic field of intensity’.[39] In order to avoid misunderstandings under the delicate social situation where uprootedness and eradication of national identity would have resonated too readily with Soviet identity officially propagated for the preceding decades, it was seen necessary to bring in a clear distinction between a nomad and a migrant, the latter described as a picaroon only taking advantage of the already existing amenities whereas the nomad is a drifter completely beyond concepts of nations and nationalities.[40] The necessity to retain individual freedom that exceeds beyond the seemingly undisputable social goals was explicitly declared by Krull: ‘I’m not going to accept even the best kind of Estonian society if this society claims itself of being a higher value than myself.’[41] What the nomads have to offer with their technological rites is a heightened bodily presence and awareness of the present: ‘an absolutely free negativity – an empty wind blowing through your pants with nobody knowing what will be the country they will live in tomorrow. … It is nothing else than the same freedom, bleak and unsecure, that currently exists outside the Art Hall.’[42]

George Steinmann’s Revival of Space:

a crossbench practitioner in the republic of historians

Yet the Art Hall as an institution was not content with manifesting this kind of bleak freedom but surely had ambitions of playing a much more important role in the establishment of a public sphere for the young democracy. Instead of a total experimental freedom largely stemming from the dilapidated state of the building where there was almost nothing to lose, there existed a desire for a much more presentable institution worthy of representative exhibitions, to say nothing of the poor working conditions and actual lack of space both for exhibiting and storing art. The hopes for positive future scenarios were high if disputable, looking for possibilities to venture into for-profit activitites to become economically self-sustained. Thus at the same time when Group T was romping in its halls, the chairman of the Estonian Artists’ Association Ando Keskküla had commissioned one of the top architecture offices, Jüri Okas and Marika Lõoke to draw up two versions of preliminary design for building an extension to the back yard of the Art Hall.[43] Drafted in 1992, the first option placed the annex behind the main hall, stretching up to the historical city wall; the second version attached a narrow extension, five stories high, to the side wall of the main hall.[44] The annex would have housed exhibition halls, storage rooms, and a café-club with open-air terrace. Characteristic to Okas-Lõoke’s sober style, the annex is rendered in a neomodernist manner with rows of strip windows, a slightly protruding rounded staircase, and a pilotis referencing to the two columns in front of the Art Hall, the only occasion of using the corbusian pilotis motif in 1930s Estonian modernism. However, the project lacked financial backing and remained unbuilt as so many other optimistic designs of the same years.

Far from building an annex, the first years of the 1990s were financially more than unsecure for the Art Hall. Initially, in 1991 with the establishment of the Art Hall as a legal body, it was financially supported by Estonian Art Foundation, a subunit of the Estonian Artists’ Association who also authorized the Art Hall’s exhibition schedule and other activities. But the tax incentives initially granted to the Art Foundation were discontinued a year later and from then on its financial support was confined to paying the bills of electricity and central heating. The Art Hall was to find financial means for its exhibitions and activtities by itself, applying for support from the Ministry of Culture, Tallinn city government, or earn it by depositing artworks from its collection.[45] The budget was extremely tight, to be slightly alleviated only with the establishment of the Estonian Cultural Endowment in 1994, with some voices even proposing that the Art Hall should go entirely to the possession and custody of the Endowment.[46]

A most unexpected turn of events came with a short visit of Swiss artist Georg Steinmann to Tallinn in September 1992. Coming with the help of Pori Art Museum’s director Marketta Seppälä, out of curiosity like a lot of foreigners at the time to see a country in turmoil of transition, upon seeing the premises of the Art Hall with Anu Liivak, Steinmann instantly envisaged an artistic intervention as a processual sculpture in the form of renovating the building to its original state. Steinmann has described his first visit to Tallinn and the Art Hall in somehow dystopian terms, remembering it as a small town with non-lit streets in the dark September evening, the Art Hall majestic but severely dilapidated, with broken windows, dysfunctional lightning, and out of order toilets.[47] His response to the situation was deeply emotional as much as it was highly rational and calculated – to initiate a renovation project of the building, presented as a processual work of art, and executed by the means of Swiss structural aid funds intended for helping Eastern European countries’ transitioning to democracy and capitalist economy. Steinmann’s initial proposal to Anu Liivak includes a conceptual diagram called ‘Mind map’ and an artistic credo detailing the diagram, titled ‘An approach towards a System of Ethics for the Future’.[48] He describes his approach as primarily locational, deeply rooted in the initital encounter with a particular space, and driven by intuitive knowledge, ‘a primordial or inborn knowledge that is more fundamental than knowledge accumulater later’.[49] Steinmann, a conceptual artist who had initiated and executed installations and various transdisciplinary projects in institutional locations as well as in the public space since 1979, sets the Art Hall project as well as his artistic endeavours in general into an all-encompassing ethical framework of sustainability, informed by global considerations and aimed at fostering a collectivity rather than pursuit of his own artistic ego. He sees himself primarily as a catalyst of processes that should lead towards a transformation: ‘In the next few decades we face an acute shift of perceptions. It stems from a host of crises – environmental, climatic, technological, economic, social, and political. Beyond doubt it promises to be the biggest composite crises that humanity has ever faced. If we do not act promptly and vigorously, we risk an even tighter bottleneck, streching into an indefinite future. But if we measure up to the challenges ahead, we shall enter on to a future that likewise will far surpass anything humanity has ever known. /…/ The present world’s challenges demand collaboration way beyond the recent experiences of citizens and politicians alike. We do not lack the means, but we are hopelessly short of vision. Thus, we all need to engage in a ‘growth spurt’ if we are to attain the giant stature that alone will match the giant rates of change around us. Nothing less will restore our ‘ecolibrium’.’[50]

Steinmann valued highly the sustainability aspect of the project, embodied in the idea of restoring something of an existing value, and of helping to create a community, enabling future artistic projects to build upon his intervention. Indeed, among the documents preserved as the archive of the project is a copy of 1992 United Nations Rio de Janeiro Earth Summit final resolution, a major global event dedicated to a critical look upon current modes of production and to finding more sustained economical approaches, leading to the infamous climate change convention. There are also copies of articles from the German and Swiss media referencing the summit and its resolutions, most likely used by Steinmann as an additional tool of persuasion in his lobbying for the Art Hall project among Swiss authorities.[51] However, in the beginning of 1990s environmental art was far from mainstream, and resonated even less in Estonia. Sure, campaigning for environmental protection had been a big part of civic activism during 1980s perestroika, taking a form of protecting the country from devastating Soviet economic interests aiming at large-scale mining with high natural costs, but refraining from creating something new as a reaction to global overproduction was an artistic position quite remote in the context of a newly independent post-Soviet state dreaming of indulging on the goodnesses of capitalist consumerism instead.

At the same time, the aspect of restoring built heritage resonated heavily. Estonian 1930s functionalism, of which the Art Hall is one of the most remarkable examples, had a notable revival already in the 1970s with the architects of the Tallinn school returning to its aesthetic in the form of neofunctionalism as an act of resistance to Soviet mass production of architecture, celebrating the centennials of notable functionalist architects, beginnings of research, and the like .[52] Obviously, the 1970s turn towards functionalist heritage signified something much wider – it meant cherishing pre-war independence era cultural values and, for the more daring, the idea of souvereignity, grandly described as an ‘idea of national independence embodied in stone’.[53] With reestablishment of independence, these connotations grew even stronger. Architectural production went through a so-called third phase of functionalist aesthetics[54], supported by heavy promotion in professional as well as mainstream media where in addition to national connotations, white functionalism acquired overtones of progressiveness and economic success.[55]This also meant reactualization of the 1930s heritage, with intensified research supported by the establishment of the Museum of Estonian Architecture in 1991, largely dedicated to research and preservation of 20thcentury architecture, and even more, by inititating the national working party of DoCoMoMo international. They jointly organized a survey exhibition of Estonian functionalism and neofunctionalism at the Finnish Museum of Architecture and Tallinn Art Hall in 1993, again an exhibition of Estonian pre-war functionalism at the Museum of Estonian Architecture in 1995, published guidebooks on 20thcentury architecture (1995) and solely on functionalist heritage (1998), and inititated a process of adding a number of buildings to the national heritage list. These activitites were embedded in a wider socio-political context characterized by a general trend of restoration and restitution. The newly independent republic was unambiguously based on legal continuity, conceptualized as restoring the previous, pre-war one instead of proclaiming a new state, and for the first years of the 1990s all the political steps taken were motivated by a desire to return to pre-war laws, traditions, and institutions, and rehabilitating everything that had been destroyed during the Soviet period – the whole tendency being so overwhelming as to substantiating a nickname of ‘republic of historians’.[56] With history used as a science of legitimation[57], everything associable with the pre-war republic could be used as a source of gaining, justifying, and preserving power in the new social situation of transition. Thus the project of restoring the building of the Art Hall became a social capital greatly enhanching the public visibility, reputation, and value of the institution of the Art Hall itself.

But initially in 1992, financial capital was a more urgent issue. After his first visit to Tallinn, Steinmann immediately committed to fundraising. The hopes were based on a basic decision of Swiss government from January 1992 to extend the list of countries entitled to Swiss monetary aid, including all ex-socialist countries of Eastern and Central Europe instead of the initial Poland, Hungary, and Czeckoslovakia; the aid limit for Estonia, allocated either as direct monetary aid or credit guarantees, was 20 million Swiss franks. The initial response Steinmann received from Swiss foreign ministry office for co-operation with Eastern Europe (Departement für Auswärtige Angelegenheiten, Büro für die Zusammenarbeit mit Osteuropa, BZO) was negative.[58] But in December 1992 the Estonian and Swiss governments had signed an agreement for the granting of non-reimbursable financial assistance to help Estonia transition to a market economy and mitigate the economic and social cost of adjustment. The contribution was to be utilized for priority infrastructure and rehabilitation projects with particular emphasis to be given to projects in the social, health care, environment and infrastructure sectors and to projects favouring the development of the emerging private sector of the economy. A cultural object like the Art Hall, not to mention an art project like it was framed by Steinmann, was clearly none of these. But the Office for Foreign Economy (Bundesamt für Aussenwirtschaft, BAWI) that was to deal with distributing the contribution explained Steinmann that essentially, the choice of projects depended primarily on the preferences of the Estonian government. So the head of the Art Hall Anu Liivak, backed up with several letters of support from various Swiss cultural institutions affirming the credibility of Steinmann[59], managed to persuade the Office for Foreign Cooperation at the Estonian Ministry of Finance to declare restoration of Tallinn Art Hall a national priority project, effectively making it the first project to gain assistance from the infrastructure funds of the Swiss monetary aid.[60] Negotiations and budgeting went on for the first half of 1993, and by September the project got a preliminary financing approval with money to be obtained in two parts, first for the design and preparatory stage, and upon presentation of a detailed budget of the construction works and contracts for the additional money to be obtained from the Estonian side the second part would be paid; by the end of December the deal for financial aid of 137000 Swiss francs was signed. Simultaneously there were negotiations with Tallinn city government for additional financing, and the Art Hall organized a charity auction counting on the solidarity of Estonian artists although as it happened, only 25 artists were willing to donate their works.[61]

By the beginning of 1994 architecture historian Liivi Künnapu had complied a detailed historical overview of the building together with special conditions for heritage conservation, and by April interior architect Rein Laur had drawn up a reconsctruction design project. In the beginning of September 1994 the actual works started involving restoration of the glass ceiling of the main hall with substitution of new non-breakable light-diffusing glasses; restoration of all original wooden framed windows except the main façade window where a new metal-framed one from Finland was required; restoration of all interior doors, walls and ceilings, cloakroom furniture, stairs and the impressive wooden bench; installation of new oak parquet floors to the exhibition halls and stairs and a linoleum floor to the foyer to substitute the original terrazzo floor; and installation of new tile floors and new sanitary equipment to the toilets .[62] A precondition for the Swiss aid was that all necessary construction materials, paints, varnishes, sanitary equipment and the like would be ordered from Swiss companies[63]; it coincided also with Steinmann’s firm wish to use only the most ecological finishing materials that were not possible to obtain from Estonia yet.[64] Initially, the project did not involve restoring of the exterior of the building but in the course of the works it turned out that the contrast would be too stark and render the remarkable efforts in the interior futile; also upon changing the façade window it turned out that there are significant cracks in the façade that definitely require fixing. On these grounds, and also because of the rise of all local costs and salaries for all the workmen, Steinmann managed to secure additional financing from BAWI in the amount of121000 Swiss francs for the local works plus 25500 francs to be paid directly for the Finnish company delivering the façade windows.[65] In addition the Swiss and Estonian governments reached an agreement that the Swiss goods and materials sent for the Art Hall would be exempted from customs duty.[66] Under these conditions, regardless of minor misunderstandings mainly between the Art Hall and the interior architect, the works were carried out according to schedule, and the festive opening of the project Revival of Space took place on February 15th, 1995 with probably the highest ranks of local and international officials, politicians and diplomats an art event had ever seen attending in Estonia.

George Steinmann’s activities in conceptualizing the project and especially in negotiating the various involved parties including the Art Hall, the Estonian Artists’ Union, Tallinn city government, Estonian Ministries of Finance and Culture, art and architecture professionals and different construction companies from the Estonian side, and Swiss embassies, Ministries of Culture and Foreign Economy, Swiss Union of Artists, Sculptors and Architects, Bern city government, Pro Helvetia foundation, and numerous private individuals from the Swiss side, clearly exceeded the conventional frameworks of an artistic project. This high-level participatory process was rather executed from a position that Markus Miessen has called that of a crossbench practitioner – essentially, an uninvited outsider.[67] According to Miessen, a crossbench practitioner is an independent and pro-active individual with a conscience, intervening into social and political processes without an appointed political mandate, retaining an autonomy of thought, proposition, and production. This role entails that in a given context one neither belongs to nor aligns with a specific party or set of stakeholders, but can openly act without having to respond to a pre-supposed set of protocols or consensual arrangement.[68] For Miessen, writing from the perspective of today’s social and political situation, the conceptualization of a crossbench practitioner serves the purpose of criticizing a general acceptance of consensus-based democratic processes unable to effectively serve its purpose, building upon Chantal Mouffe’s understanding of consensus as inevitable violence and her calls for more antagonistic modes of participation in the social processes.[69] In the context of the transition of the beginning of the 1990s Estonia, the protocols and regulations of initiating processes were still in the making and the social and political landscape was much less institutionalized, generating a real possibility for such a crossbench intervention. One can also not underestimate the Swiss background of Steinmann, stepping in from a country with a tradition of very specific direct democracy investing its citizens with a confidence in such possibilities. The fact that the Swiss government was willing to enter into legal agreements involving finances of such amounts with Steinmann as a private individual, the artist acting as an institution in itself, also demonstrates the unusual level of particpatory politics possible. The model was also used in Steinmann’s later projects, most notably for a project in Komi where he negotiated the local people and institutions, Finnish architects Heikkinen-Komonen, and Swiss financial aid measures to build up a centre for sustainable forestry.[70] In both cases, Steinmann developed a project that through the processes of its execution created a new type of public participation, empowering the participants in new and previously unexisting ways, and thus remarkably extending the existing public sphere. In the case of the Art Hall, the process of building up a network did not stop with the completion of the renovation process but involved also facilitating Anu Liivak’s research trip to Swiss cultural institutions two years later in the name of building up further contacts for the future programming of the Art Hall.[71] While Steinmann stresses that his practice primarily emanates from the encounter with a particular place[72], it is clear that place for him is not merely a physical location but rather a complex discursive entity, best characterized with the help of Doreen Massey’s definition as ‘a constellation of social relations, meeting and weaving together at a particular locus /…/ which includes a consciousness of its links with the wider world, which integrates in a positive way the global and the local.’[73]

Such caring for the institution’s well-being after his own project in its strict terms had ended for some time already, as well as the fact that the documentation of the Revival of Space as assembled for later display at the Kunstmuseum Bern archives[74] includes also photographs of various exhibitions that took place at the Art Hall after the renovation, testify unambiguously that for Steinmann, the work was primarily processual, a ‘growing sculpture’ as he called it[75], serving as a catalyst for future events and various user groups; in that sense, the following exhibitions of the Art Hall effectively became part of his work. At the same time, exhibiting the empty space as a work in itself with a grand opening, invitations and posters and regular opening hours for a normal duration of exhibition, embeds the project in the tradition of gestures of void starting with Yves Klein at the Iris Clert gallery in Paris 1958[76] and continuing with Robert Barry, Robert Irwin, Michael Asher, Laurie Parsons and many others, exploring the possibilities of exhibited empty space from the perspectives of human perception, institutional critique, artistic ethics, issues of readymade, and more.[77] Whereas leaving a gallery empty would most readily resonate with institutional critique, at first glance the case of the Revival of Spaceseems to be the opposite, as the institution most directly benefitted from the project that remarkably facilitated its ensuing operation in the mainstream art world. Indeed, a project directly inspired by the Revival of Space, Maria Eichhorn’s Money at Kunsthalle Bern (2001) which similarly consisted of building renovation for the budget allocated for her exhibition, has been discussed in terms of the artist’s willingness to let herself be instrumentalized.[78] However, the critical stance of Steinmann’s project lay specifically in its durational dimension that involves open-endedness and enables materialization of future projects that may cohere cumulatively, creating a spatio-temporal constellation of artworks and projects over time – a durational approach that has been seen as one of the most sensible and fruitful strategies in terms of art addressing the public sphere.[79]

Still, during the Revival of Space as an exhibition of immaculate empty white artspace it seems that the affective qualities of the space dominated in the viewers’ experiences. The notes and comments left in the exhibition’s guestbook mainly praise the renovation works and thank the financers, or remark upon the revealed beauty of the building or certain architectural details, testifying of the primarily aesthetic perspective the project was publicly seen from.[80] The reviews also mostly praise the excellent quality of renovation works and superb spatial experience of the halls, primarily appreciating Steinmann’s project as an enormous practical and material gain, something one can only dream to happen to other cultural institutions in critical conditions as well.[81] Indeed, calling Steinmann ingenuous[82] and his project a welfare society’s act of redemption and goodwill[83], perhaps masked an inferiority complex in the face of such amount of foreign money but naturally also acknowledged the inevitable neocolonial nuance of such structural aid projects. The domination of aesthetic dimension and perception of spatial qualities in the reception of the work was further increased by the Art Hall itself, deciding to incorporate to the duration of the Revival of Space additional performances by Aili Vint who staged painting and light installations to the so-called altarspace of the main hall.[84] In that sense, the display of the empty premises was embedded on the one hand, in the discourse of architecture renovation, and on the other, that of a spectacular spatial experience conforming to the so-called experiential turn,[85] more or less downplaying the aspects of durational participatory practice, sustainability in the face of global ecological issues, and the artist’s ethical stance hoping for art to fill the void in a post-religious era.[86]

However, by restoring the architectural premises of the Art Hall to its original glory, the project also effectively restored the original conventions of a white cube exhibition space. In its purity and whiteness, especially in contrast to the other, more or less Soviet-flavoured art spaces in town, the Art Hall stood out as the space where art could start to reclaim its position as an agent in the construction of the public sphere and a serious topic of conversation (an ambition that was further reinforced by the quite lavishly funded exhibitions of the Soros foundation for contemporary art importing a new discourse of art as social commentary[87]) as well as a commodity in the market. The new and shining premises together with the contacts aquired in the process surely marked a new level of performance for the institution. The restored aesthetic of the building had a major role to play in elevating art’s position in the eyes of non-art society but it did so with a price of losing some of its subversive potential. The completion of the renovation coincided with certain calming down of social processes, with the end of the transition as the time of radical openness, and art, too, was expected to give up some of its transgressiveness. The renovation of the premises also implied at restoration of certain behavioural conventions. Indeed, the set of dcoumentation of the Revival of Spacekept as an artwork in itself in the Kunstmuseum Bern includes historical photographs not only of the building but also of the social life that took place in the building in the 1930s with formally dressed male artists posing in front of the Art Hall, people partying in the club downstairs, and the like, nostalgically implying at returning to not only the original purity of the spaces but to the social life generated by them as well.[88] This intimate connection was not lost with the reviewers, noting: ‘The Art Hall is beautiful like memories of the pre-war republic – decent youth, cafés without alcohol, national home embellishment campaigns, academic corporations, vacations in Narva-Jõesuu, recurring thank you and you’re welcome…’[89]

Conclusion

As seen from the above, in the beginning of the 1990s Tallinn Art Hall hosted art projects with very different agendas and different strategies regarding art’s participation in the processes of construction of a public sphere, and art’s position in relation to the simultaneously unfolding social processes of the transition state. In the cases analyzed here, addressing the architectural space of the Art Hall as well as art’s ability to engage various groups of people were essential in forming a new understanding of an art project’s potential to participate in social processes. Also, in both cases time, or the durational aspect of the projects, emerged as an important factor in forming new type of communities. In the case of the performances of Group T, the continuous events unfolding over a week or two managed to construct a new type of relationship between art and its public, forming a temporary congregation that may be described as a community eschewing a singular denominator, a being-togetherness that does not necessarily assume nor entail sharing common values, principles, or goals – quite the contrary, its potential as a political position lies specifically in its absence of goals projected towards future. In the face of the mainstream social agenda being building up a restitutive republic, and tightening the belts and squaring the matters in the name of a historically just and prosperous society to come in some undefined near future, this being-togetherness as a temporary counterpublic sphere offers an alternative that values the present moment instead, and acknowledges a whole spectrum of human impulses. At the same time the Revival of Space project assumes an active role in the enfolding processes of building up of democratic society, making an idealistic example by intervening from a position of an uninitiated outsider with a conscience, and under the circumstances of openness of the transition era, achieves in bending the not-yet-rigid institutional frameworks to its advantage. The project, unfolding over three years, manages to build up previously unexeistent networks between the spheres of art, politics and finance, broadening the scope of operation of all participating entities, and acting as a catalyst for future cooperations and projects. At the same time, the immaculate restoring of the premises of the Art Hall incurred reinstation of classical white cube conventions as well, contributing to reframing art in terms of the aesthetic. Internationally, in the 1990s art institutions were painstakingly reinventing themselves to be seen not as passive depositors and exhibitors of the artworks but to have an essential role as sites of production, and, in terms of public, to produce active participants instead of passive enjoyers. In the case of the Art Hall, the actions of Group T fulfilled those goals brilliantly but it seems the Art Hall was not ready to build upon these developments but opted for a return to more conventional and more representative relationship of art, space and the public with the possibilities generated by the Revival of Space. The reasons were obviously practical as well as ideological, following the developments of the young democratic society itself.

[1]Hasso Krull. Ei juhtunud midagi (Eleonora). – Vikerkaar 4/1993, p 50.

[2]Hasso Krull. Nomadistlikud rituaalid. – Eesti Ekspress 15.02.1991.

[3]Heie Treier. Kunstnik: Narr ja nomaad. – Kunst 1/1991, p4–5.

[4]Vappu Vabar. Salapärane performance. – Teater. Muusika. Kino 7/1991, pp 76–77, 96–97.

[5]Hanno Soans. Peegel ja piits. Mina köidikud uuemas Eesti kunstis. – Kunsti-teaduslikke uurimusi 10/2000, pp 309–353.

[6]Hasso Krull. Nomadistilikud rituaalid.

[7]Hasso Krull. Postnomadonoomia. – Vikerkaar 6/1991.

[8]Hasso Krull. Nomadism repeated. – Eesti Ekspress 19.02.1993.

[9]Heie Treier. Dessantlased on vallutanud Kunstihoone! – Sirp 15.03.1991.

[10]Vappu Vabar. Salapärane performance.

[11]Vappu Vabar. Urmas Muru. Jutuajamine näituse “Olematu kunst” kuraatoriga. – Kultuurileht 9.12.1994.

[12]Bernard Tschumi. Spaces and Events. – Bernard Tschumi. Architecture and Disjunction. Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 1996, p 139.

[13]Eesti nüüdiskunst: Rühm T. ETV 1997. https://arhiiv.err.ee/vaata/eesti-kunst-ruhm-t, accessed 31.03.2018.

[14]Dennis Hollier. Against Architecture. The Writings of Georges Bataille. Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 1995, p 9.

[15]Conversation with Urmas Muru, 18.10.2017.

[16]Raoul Kurvitz. Pöörasustes sissepühitsetud {sulud}. – Agent. Eesti Kunsti-muuseumi ajaleht 11 (juuli)/2007, p 14.

[17]Vaike Sarv. Sovetliku šamaani raske roll. – Teater. Muusika. Kino12/1990, pp 16–19; Vappu Vabar. Salapärane performance.

[18]Heie Treier. A. H. Tammsaare majamuuseumis. – Sirp ja Vasar 3.07.1987.

[19]Urmas Muru. Rühm T. – Noorus 12/1987, pp 48–49.

[20]As stated in Heie Treier, Tammsaare majamuuseumis, op cit.

[21]The authors of A Guide to Intronomadismperformances were listed as: Raoul Kurvitz, Urmas Muru, Peeter Pere, Tarvo Hanno Varres, Maria Avdyushko, Ariel Lagle, Allan Hmelnitski, Raul Saaremets, Hasso Krull, Eve Kask, Teet Parve; additional participants were listed as: Young people from the front of café “Moskva”, A. Veskiväli, E. Kask, H. Liivrand, A. Juske, K. Kivi, T. Pedaru, A. Saaremets, art students of R. Kurvitz and E. Kask (L. Šaldejeva, P. Raudsepp, H. Kont, I. Simm, R. Aus, L. Kuutma) and others. – Appendix to Hasso Krull. Postnomadonoomia. – Vikerkaar 6/1991, p 44.

[22]Conversation with Raoul Kurvitz, 6.12.2012.

[23]Conversation with Tarvo Hanno Varres, 6.10.2017.

[24]Conversation with Teet Parve, 10.01.2018.

[25]Conversation with Urmas Muru, 18.10.2017.

[26]Ibid.

[27]Vappu Vabar. Salapärane performance, p. 77.

[28]Conversation with Tarvo Hanno Varres.

[29]Airi-Alina Allaste. Klubikultuur Eestis. – Ülbed üheksakümnendad. Probleemid, teemad ja tähendused 1990. aastate Eesti kunstis. Tallinn: Kaasaegse Kunsti Eesti Keskus, 2001,p. 69.

[30]See more Margaret Tali. Kunstnik kui popstaar. Raoul Kurvitz ja Mark Kostabi 1990. aastate Eesti meedia diskursustes. – Kunstiteaduslikke uurimusi 1–2/2007, pp. 143–169.

[31]https://arhiiv.err.ee/samast-seeriast/elustiilid-techno/default/1, accessed 31.03.2018.

[32]The manifesto was published in a leaflet Eesti ekspressionistlik arhitektuur 1985–1988(Tallinn: RPI Eesti Tööstusprojekt, 1988), unpaginated; and later republished in the cultural monthly Vikerkaar 10/1989.

[33]See eg Eesti Ekspress 29.04.1994, 20.05.1994, 17.06.1994.

[34]See Pirjo Turk. Eesti punk. Miilitsast presidendini. – Airi-Alina Allaste (ed). Subkultuurid. Elustiilide uurimused. Tallinn: Tallinna Ülikooli Kirjastus, 2013, pp 79–118.

[35]Michel Gaillot. Multiple meaning. Techno: An Artistic and Political laboratory of the present. Paris: Editions Dis Voir, s.a, p. 18.

[36]Ibid, p. 24.

[37]Ibid, p. 21.

[38]Interview with Jean-Luc Nancy. – Michel Gaillot. Multiple Meaning. Techno: An Artistic and Political laboratory of the present. Paris: Editions Dis Voir, s.a, p. 87.

[39]Hasso Krull. Postnomadonoomia.

[40]Hasso Krull. Nomadistlikud rituaalid.

[41]Intervjuu hr. Hasso Krulliga. – Magellani pilved, 1/1993, pp. 44–62.

[42]Hasso Krull. Postnomadonoomia.

[43]Anu Liivak. Tagasivaade 1990. aastate kunstimaastikule. – Valiku vabadus. 1990. aastate Eesti kunst. Tallinna Kunstihoone, 1999, p. 33.

[44]For the drawings see Karin Hallas-Murula. Tallinna Kunstihoone 1934–1940: ehitamine ja arhitektuur. Tallinn: Tallinna Kunstihoone Fond, 2014, pp. 128–129.

[45]Intervjuu Tallinna Kunstihoone intendandi Anu Liivakuga. – Metroo 1/1994, p. 5.

[46]Karin Hallas. Kunstihoone ja Kultuurkapital. – Rahva Hääl, 16.02.1995.

[47]Conversation with George Steinmann, 1.12.2017.

[48]George Steinmann archive at the Bern Art Museum. A.2007.100/097

[49]Ibid.

[50]Ibid.

[51]George Steinmann archive at the Bern Art Museum, A.2007.100/097.

[52]See Mart Kalm, Krista Kodres (eds). Teisiti: funktsionalism ja neofunktsionalism Eesti arhitektuuris. Toisin : funktionalismi ja neofunktionalismi Viron arkkitehtuurissa. Tallinn: Museum of Estonian Architecture, 1993.

[53]Leonhard Lapin. Funktsionalism ja rahvuslik identiteet. – Ehituskunst 15/1996, p. 2.

[54]See Ingrid Lillemägi. Valgete majade kolmas tulemine. – Maja .3/2002, pp. 18–21.

[55]See Epp Lankots. Eesti ärieliidi enesekirjeldusmudelid ruumilises keskkonnas. – Eesti kunsti sotsiaalsed portreed. Lisandusi Eesti kunstiloole. Tallinn: Kaasaegse kunsti Eesti keskus, 2003.

[56]Marek Tamm. The republic of historians. Historians as nation builders in Estonia (late 1980s – early 1990s). – Rethinking History, 2016, 20:2, pp. 154–171.

[57]Ibid.

[58]George Steinmann archive at the Bern Art Museum, A.2007.100/096.

[59]Ibid.

[60]Conversation with George Steinmann, 1.12.2017.

[61]Anu Liivak. Tagasivaade 1990. aastate kunstimaastikule, p. 34.

[62]Aruanne Tallinna Kunstihoone restaureerimis- ja rekonstrueerimis-töödest 1994–1995. Koostanud arhitektuuriajaloolane Liivi Künnapu. Tallinn, 1995. Archive of Tallinn Urban Planning Department.

[63]Ibid.; George Steinmann archive at the Bern Art Museum, A.2007.100/096.

[64]Conversation with George Steinmann, 1.12.2017.

[65]Amounts stated in contracts kept in Steinmann’s archive at the Kunstmuseum Bern. In a lecture held in Tallinn on January 10th, 2016 Steinmann has said that the total costs of the renovation were 455000 CHF, of which 415000 CHF amounted to Swiss monetary aid.

[66]George Steinmann archive at the Bern Art Museum, A.2007.100/096.

[67]See Markus Miessen. The Nightmare of Participation. Crossbench Praxis as A Mode of Criticality. Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2011.

[68]Crossbenching. Interview with Markus Miessen. – Common. Journal für Kunst & Öffentlichkeit. Konjunktur und Krise No 2, 2013. http://commonthejournal.com/journal/konjunktur-und-krise-no-2/crossbenching-interview-with-markus-miessen/, accessed 29.03.2018.

[69]See more Nikolaus Hirsch, Markus Miessen (Eds). Critical Spatial Practice 2. The Space of Agonism. Markus Miessen in Conversation with Chantal Mouffe. Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2012.

[70]Helen Hirsch. Von Heidelbeeren und Menschen. – Call and Response. George Steinmann im Dialog. Zürich: Scheidegger & Spiess und Kunstmuseum Thun, 2014, pp. 15–19.

[71]George Steinmann archive at the Bern Art Museum, A.2007.100/096.

[72]Ruumi naasmine. George Steinmann. Tallinna Kunstihoone. Catalogue. s.l.: George Steinmann, 1995; see also Mind map. George Steinmann archive at the Bern Art Museum, A.2007.100/097.

[73]Doreen Massey. A global sense of place. – Trevor Barnes, Derek Gregory (eds). Reading Human Geography. London: Arnold, 1997, pp. 315–323.

[74]George Steinmann archive at the Bern Art Museum, A.2007.100/089; A.2007.100/092; A.2007.100/083; A.2007.100/085; A.2007.100/086; A.2007.100/076; A.2007.100/077; A.2007.100/078.

[75]Helen Hirsch. Von Heidelbeeren und Menschen.

[76]The Specialization of Sensibility in the Raw Material State of Stabilized Pictorial Sensibilty[la spécialisation de la sensibilité àl’état matière première en sensibilité picturale stabilisée], usually referred to as The Void,was a work where Yves Klein removed everything in the gallery space except for one cabinet, painted all surfaces white, and staged an elaborate opening ceremony. This work is generally considered the first occasion of exhibiting an empty gallery.

[77]See Voids. A Retrospective. Zürich: JRP/Ringier Kunstverlag AG, 2009.

[78]Mai-Thu Perret. Building Works at Kunsthalle Bern. – Voids, A Retrospective. Zürich: JRP/Ringier Kunstverlag AG, 2009, pp. 147.

[79]Paul O’Neill, Claire Doherty. Introduction. Locating the Producers. An End to the Beginning, the Beginning of the End. – Paul O’Neill, Claire Doherty (eds). Locating the Producers. Durational Approaches to Public Art. Amsterdam: Valiz, 2011, pp. 1–15.

[80]See more Siim Preiman. Kaasaegse kunsti publikuretseptsioon 1990. aastail Tallinna Kunstihoone näitel. Bakalaureusetöö. Eesti Kunstiakadeemia Kunstiteaduse instituut. Tallinn, 2015, pp. 28–32.

[81]Kunstihoone õnnelik saatus. – Rahva Hääl 16.02.1995.

[82]Sisu: 12. Ruumi naasmine. https://arhiiv.err.ee/vaata/sisu-12, accessed 31.03.2018.

[83]Meelis Kapstas. Remont kui kunstiteos. – Päevaleht, 16.02.1995.

[84]Üks pilt. Aili Vint: Skulptuur päikeseloojangust. ETV 1995. https://arhiiv.err.ee/vaata/uks-pilt-aili-vint-skulptuur-paikeseloojangust, accessed 31.03.2018.

[85]Dorothea von Hantelmann. The experiential turn. – Walker Living Collections Catalogue. Volume I. On Performativity. Walker Art Center, 2014. http://walkerart.org/collections/publications/performativity/experiential-turn/, accessed 31.03.2018.

[86]The latter is perhaps most clearly expressed in Steinmann’s essay comprising of quotes by the painting philosophy of Shin Tao, see George Steinmann. Ruumi naasmine. – Ehituskunst. Estonian Architectural Review no 12, 1995, pp. 5–9.

[87]Sirje Helme. Sorose Kaasaegse Kunsti Eesti Keskus keerulisel kümnendil. – Ülbed üheksakümnendad. Probleemid, teemad ja tähendused 1990. aastate Eesti kunstis. Tallinn: Kaasaegse Kunsti Eesti Keskus, 2001, pp. 36–52.

[88]George Steinmann archive at the Bern Art Museum, A.2007.100/005; A.2007.100/008.

[89]Harry Liivrand. Vabariigi naasmine. – Eesti Ekspress 23.02.1995.

Add a comment