Tõnis Vint’s vision for Naissaar island: An extraterritorial utopia zone of the transition era

The beginning of the 1990s were the years when the rules and conventions of the newly reindependent Estonian society were still in the making. The country, having reestablished itself as an independent democratic state in 1991, was striving to make up for the years lost as a member state of the Soviet Union, meaning a simultaneous aim at realigning the policies with contemporary Western European models and continuing the legacies of pre-war Estonian Republic, resulting in a certain internal tension in consolidating these quite different desires. Socially, establishing itself as a democratic state also meant establishing a public sphere consistent with the principles of an open democratic society – a process that had certainly begun with perestroika and glasnost of the end of the 1980s and continued with civic activism in the form of environmental and heritage movements and the resulting national liberation processes but was far from having settled into an inclusive sphere of rational deliberation and generally accepted protocols. The public sphere was rather in an active and antagonistic process of making, a process shaped by, among else, certain artistic projects claiming social relevance.

The current article is focused on one such artistic project: an urban vision for Naissaar island by artist Tõnis Vint who was intensely working on this conception in the years 1992 – 1996. The aim is to look at the project simultaneously as a continuation of his earlier artistic practice as well as an agent in the period’s social and economical processes, illuminating it as an intersection of a spiritual and utopian artistic endeavour on one hand, and a practical attempt at intervening into real urban planning processes of this fiercely neoliberalist era on the other. Tõnis Vint’s vision for Naissaar emerges as a very characteristic case of the transition era which in the one hand opens up a space for public discussion on a previously unimaginable scope, and on the other hand demonstrates how an artistic position that had great critical potential during the Late Soviet period may become prone to be levelled out and applied to the benefit of different neoliberal interests. As such, Naissaar vision is also a case of looking closer at the internal incoherence of artistic practices of the transition era, displaying characteristics of both the Late Soviet and the postsoviet times, and a case for arguing for a more specific, more detailed and nuanced analyse of the processes of transition.

First years of the 1990s: post-Socialism, transition, or interregnum

Lately there have been many voices calling for a critical reconceptualisation of the notions of transition as well as the term post-socialist. Both the beginning and end dates of transition appear under scrutiny, not to mention the scope of its possible content and meaning.[1] The majority of the discourse so far has approached the term from the point of view of “return to normalcy”, looking at the developments of post-socialist societies from the perspective of a normative West. The peculiarities of the transition are measured as either lagging behind or sufficiently fast, presumably at some point “arriving” at a level where the peculiarities and differences will be erased, the transition completed, and thus, the term post-socialist may be dropped as not adequate any more – it only remains a question of discussion when and on what grounds this happens. However, this perspective is quite reductionist and hinders analysing the phenomena on their own terms, as agents constructing a historical specificity valuable on its own, which is also why I’m using a term “period of interregnum” rather than transition. Post-socialist conditions manifest themselves in a huge number of ways in different regions, countries, contexts, and spheres of action, and rather than looking for suitable generalizable models for all, we should be aiming at differentiating them, focusing on “actually existing post-socialisms”.[2] To understand the conditions as they are lived and experienced, post-socialism would rather be appropriate to use as a noun in plural. It has certainly been argued that the measures taken for enabling and alleviating the transition – foreign aid, investments, policies modelled on and aiming at capitalist liberal democracies – were nothing else but neo-colonialism, a swift replacement of Soviet power with Western hegemony[3], and upon will, the current case study might also be interpreted from that position. However, the phenomena of the era deserve a more nuanced reading: after all, post-socialism can be seen as not just a chronological periodization but also an epistemological one.[4]

In the case of Estonian context, the transition has been divided into five periods: beginning with the “Singing revolution” of 1988 – 1991, continuing into a period of radical reforms (1991 – 1994), economical stabilisation (1995 – 1998), negotiations of entering the eurozone (1999-2004), and new challenges and identity crisis following the EU membership (2005 – 2008).[5] This view again seems to stem from a position of transition as a directed vector of delevopment, a temporary phenomenon aimed at a clear ultimate purpose; however the benefit of this periodization is a more nuanced approach to the timespan based on actual specificities of the context. The stated period of radical reforms, 1991 - 1994 more or less correlates with other accounts of these years as displaying the greatest amount of radical openness and embodying a Lefortian concept of true democracy as an empty space where power is constantly negotiated, belonging to no one, and no markers of certainty yet exist.[6] But already in 1994, there were commentators observing a feeling of closure, of substitution of the productive openness for more rigid conventions, lamenting that the age for imagination is over.[7] So Tõnis Vint’s vision for Naissaar effectively used, and at the same time was part of creating, this unique period of unhindered imagiation and productive democracy. And it is only during such moments of resistance or radical reimagination of space when reappropriation of (public) space actually creates public sphere, as it must be kept in mind that public space does not inevitably correlate with public sphere but is more often than not a vehicle for representing officially accepted values rather than a true space for negotiation.[8] Afterall, creating public sphere as an arena for truly negotiating the lecagies of the late socialism and the transition as well as for conceptualising the present moment and imagining the paths for the future was one of the main aims and urges of artistic practices over the whole Eastern Europe, so much so that Piotr Piotrowski has summarized the period with the term “agoraphilia”.[9]

Naissaar: the city of the future

Tõnis Vint was one of the most avant-garde artists of the Late Soviet Estonia who in the 1960s-1970s had established himself as a prolific visual artist, graphic designer, and one of the spiritual leaders of a generation of artists and architects aesthetically and socially revolting against the canons of Soviet life. His practice was characterized by an astonishing complex of interests and inspirations ranging from Pop Art and Art Nouveau to Baltic and Celtic folk art, to aesthetic and semiotic systems of China, Japan, and India. From the late 1960s onwards, Vint’s apartment was a locus for regular meetings of Tallinn’s artists and intellectuals, with frequent visitors from Moscow alternative art scene and elsewhere, becoming an important site for discussions and exchange of information and creative impulses that by the end of the 1980s had at the same time evolved into something of an alternative education for a devoted group of disciples. Whereas in the Late Soviet times Vint’s own artistic production had been mainly focused on two-dimensional art and graphic design, the social transformations related to the dissolving of the Soviet bloc and reindependence of Estonia inspired him to pursue a project aiming at a large-scale transformation of spatial environment and a total renewal of society at large. Although the period of transition brought along an abundance of urban and architectural visions aiming at conceptualising and envisioning space for the new society in the making, Tõnis Vint’s vision for Naissaar may easily be called the boldest of them.[10] The ambition of the project is demonstrated by its architectural innovation, its scope of conceptual references as well as by media chosen for its presentation.

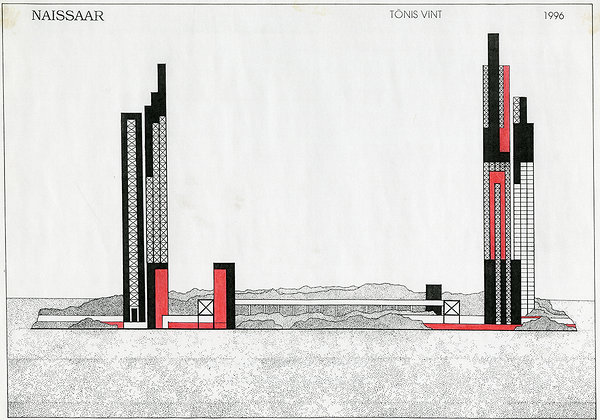

Vint’s vision for Naissaar consists of a series of drawings, accompanied by four essays explaining and promoting the idea that were published in specialist media like the Estonian Architectural Review Ehituskunst[11] as well as general media like the very popular weekly newspaper Eesti Ekspress[12], itself a marker of the era, and a popular interest montly magazine Elu Pilt[13]. Two more essays from the same period may be seen as a continuation of these ideas.[14] In addition, the project was thoroughy introduced, including lengthy commentaries by Vint himself, in an environmental broadcast “Osoon” in the national television in 1994,[15] and a year later received a full feature called “The city of the Future” dedicated to it in the same national broadcast channel.[16] The idea of the project was to establish an international centre for technology, culture and environment to Naissaar, an uninhabited island off the coast of Tallinn, devastated by the 50-year use as a Soviet military base. With different drawings testing different versions of the architectural solution, basically the new establishment was to take a form of two clusters of buildings situated in both ends of the island, with a soaring height of almost a kilometre maximum. In tune with Vint’s decades-long practice of spiritually informed art, the extraordinary height of Naissaar settlements was to serve as an accumulator of ‘cosmic energy’ and a device for urban acupuncture, healing the trauma of the Soviet past. It is most remarkable that the project was first introduced in widely circulated printed media, then came the TV broadcasts, and only then, in 1996, four years after the initial idea, was the series of drawings exhibited in a classical way in a gallery space, as part of an exhibition of Studio22 comprising of Vint himself and his disciples tackling in more and less abstract ways the ideas of future urban developments.[17] This indicates a clear intention at stepping out of the confines of artistic sphere in the classical sense of the term. Notwithstanding the project’s utopian character Vint was clearly aiming at relating it to the actual social and economical realities and at entering a polemical dialogue with publicity.

The very first exposition of the idea in a polemical article published in Eesti Ekspress set the tone: as the title “Would Naissaar be able to save Estonian top science and high culture?” suggests, the aim of the project was to establish something of extraordinary quality that would impact development of the whole nation and state. However, the article remains quite unspecific in terms of the actual spatial structure or functional programme of Naissaar – the text part rather deals with geomantics, introduced as a feng shui secret science, as a system for basing the decisions concerning urban planning principles upon. Vint is supposedly performing a geomantic analysis of the whole Tallinn, arriving at a conclusion that the Soviet-time residential areas of prefabricated tower blocks at Õismäe and Lasnamäe have been positioned ‘absolutely incorrectly’ and are thus a failure; further urban development should rather be concentrated on an axis of Naissaar island and Ülemiste lake, and Viimsi peninsula and other coastal areas. The experience of Soviet-time urbanism is negated and left behind for the new era to be able to begin but not on the due grounds of its monotonous architecture, inadequate social spaces, or inappropriate ideology but resting the claim on some primeval and thus seemingly universal and undisputable spatial forces. He continues swiftly with entering into argument with the leaders of Viimsi county – according to Estonian administrative division, Naissaar belongs to the county and not Tallinn city – accusing them of short-sightedness and petty financial motives. Such abrupt change of different rhetorical registers, mixing cosmic-universal matters and daily politics, is very characteristic to Vint’s polemical articles of the time in general, establishing a voice that seemingly speaks from a position of higher authority, assessing opportunities and dangers of contemporary decisions from some all-knowing cosmic vantage point. In this article, the larger context of future developments of Naissaar is Europe – the project is presented as an essential counterforce to spiritual and intellectual decline currently threatening the whole Europe.

With all this militant argument it is quite surprising that we only get a minimum of hints about the project itself both in terms of its content and outlook. The latter is represented by a sole drawing of a classically futuristic dense high-rise city quite different from Vint’s usual distinct and easily recognizable visual style – actually, it is Iakov G. Chernikhov’s Composition No 25 from 1929 with five Estonian national flags added on top.[18] The drawing serves primarily as a promotional image rather than an actual speculative urban vision, clearly establishing a mental affinity with the ambitions and concerns of Russian avant-garde, presumably aiming at a social tranformation of equal scale and radicality. Using Russian constructivist images for illustrating his ideas further testifies that initially, Vint was only focused on the conception and the grand structures – the geomantic relationships of Naissaar and the city, and the sole height that he wanted to see there. How to achieve that desired height, what kind of architectural and programmatic proposal would be suitable under the economic and political conditions of a newly developing society to sustain building something so high, were initially questions of minor importance.

However, in the following articles as well as when talking in the TV broadcasts the vision began to take on a more comprehensive form both in terms of function and visual style. An article published only a month later continues explaining the feng shui principles but brings the issue more to the ground by drawing analogies with Hongkong and Macao.[19] Vint provides idealistic descriptions of their economies where great revenues of entertainment industries and gambling are allegedly invested into public wellbeing, contrasting this model with greed of Estonians who would rather see the island divided into private recreational havens.[20] He also displays certain flexibility: as in 1994-1995 there also surfaced an alternative development vision, to turn the island into a semi-closed zone of environmental protection, Vint integrates the idea into his proposal. An article written in 1995 details the functional scheme as follows: the main part of the island would remain untouched landscape and the settlements in its northern and southern end would feature international banks; cultural and educational centres; information centres fostering the cooperation of sciences and arts; research institutes for futurology; and intellectual tourism.[21] All the institutions would be established in cooperation of Western and Eastern (implicitly meaning Japanese and Chinese) institutions and corporations, aiming at creating an unprecedented hub of creativity, knowledge and cooperation. Compared to articles written two years earlier, there is now much less space devoted to spiritual-esoteric concerns, the focus is rather on the practical side of the matter, and the language is more down-to-earth and talking business. This certainly reflects a surprising turn in his endeavour, to try to take the matter into his hands in a very practical way: in 1994, he compiled something of a promotional brochure, introducing not only his core idea and drawings for Naissaar but also some visual material claiming similarities in Estonian and Japanese traditional architecture as well as examples of his fellow Estonian architects like Leonhard Lapin, Vilen Künnapu and Jüri Okas and Marika Lõoke.[22] The hand-bound brochures were presented to the Japanese embassy in the hope of the diplomats passing them on to Japanese companies interested in possible investments and cooperation.[23] At the same time Vint was not free from a certain colonialist mentality, seeing Naissaar as a potential training ground for Eastern businessmen who could spend there some time learning the Western ways of business and sociality before continuing to venture to Western Europe.[24]

Visually, the project also evolved, taking on a more recognizable appearance of Vint’s approach, linking the vision to some drawings of conceptual space from his earlier career. Titling a drawing of Naissaar as the Holy Mountain rising from the sea[25], the focus still lies on its height and thrust upwards, connecting the project to his general theme of towers and futuristic cities starting already with a childrens’ book “Aastasse 2000” [To the Year 2000] from 1973 that featured an image of a highrise city with elevated expressways on the foreground. A highrise building in the form of a tower has been called one of the central elements of Tõnis Vint’s personal iconography, a visual archetype that symbolizes universal higher aspiration and ascetic devotion, a connection between the material and spiritual worlds enabling interaction with the higher level.[26] Vint has repeatedly emphasized the importance of high-rise for the advancement of society, referencing the 18th-century Swedish philosopher and mystic Emanuel Swedenborg who claimed that there is a correlation between the height of the buildings and a society’s level of mental and spiritual development[27]; but he has also spoken about certain Russian scientists who have confirmed the role of high towers as mediators of human consciousness and higher knowledge.[28] In this context, building highrises would be – as much as the whole Naissaar project – an attempt to counter a provincial and petit-bourgeois mentality.[29] This point is further made by the choice of imagery – whereas many drawings of the series depict highly abstracted orthogonal building forms that can be strongly related to Vint’s earlier spatial imagery found in his graphic works, the design of his own apartment in Mustamäe, or the stage set for Rabindranath Tagore’s play “Postimaja” (Post Office, directed by Juhan Viiding, 1983), one version of elevation of Naissaar features four images of Empire State Building, a plain reference to Manhattan as the archetypical cosmopolitan highrise city. The images of the Empire State Building may also be used for height reference – the higher versions of the vision depict buildings three to four times its height. The stunning visual effect was very important – the visual imagery of the transition era was highly charged and even more keenly observed in a culture which during the Soviet years had developed a highly sophisticated ability of reading subtle signs of allegiance or dissidence. The “Western” signs were meant as an aesthetic display of capitalism – the premiss was that capitalism was a belief, an ideology, and a system that had to be “built” in the same way as socialism was “built”.[30] However, giving an actual architectural proposal never was the aim of Tõnis Vint – quite the contrary, he insisted that designing the actual buildings should be entrusted to the most important international star architects and construction commissioned from international companies with the most up-to-date know-how in high-tech construction – all of them, he believed, eager and waiting for such an opportunity.[31] Elsewhere, he was expressing conviction that only Japanese designers would be able to handle the unique hybrid situation of untouched nature and concrete military structures.[32] The need to keep most of the island’s greeney intact, not to mention the practical problem of the island being heavily mined still in the beginning of 1990s, has in his vision resulted in an elevated expressway or suspended railway connecting the northern and southern settlements. Thus the settlements themselves would work as more or less enclaves interacting with the rest of the island as little as possible, as if forming islands within an island.[33]

‘The Zone’, or legal and economic speculations

Speaking about the pratical feasibility of his vision, Vint recurrently uses terms such as “a grand project”, “new international centre”, “new economic centre”, and talks vaguely about a new economic model. But in one article he directly states ideas by Sulo Muldia as his inspiration.[34] In 1990, a young and eager businessman Sulo Muldia wrote an article to the weekly newspaper Eesti Ekspress titled “Skyscrapers in Naissaar. Rich Estonia six years from now”.[35] With great optimism, he pictured Estonian government realizing already in a year that the legislative system drawn up following the examples of Scandinavian welfare states would not suit Estonia as a developing country, so the government must turn their heads towards Singapur and Taiwan in search of inspiration instead. With the impetus for the vision clearly coming from discontent with Estonian tax laws, Muldia proposes reforms completely abolishing income taxes and all taxes related to raw materials and export. The tax exemption was to apply for the whole of Estonia, however, a special boost would be given to Naissaar which would form a separate juristidction with regulations being made not by the Estonian government but by a board of its own, consisting of financial experts and businessmen. The situation would quickly result in developing a super project of Naissaar which would attract investors from Far East, Western Europe as well as Russia. Within six years it was to develop into a full new duty-free city, populated by all important international corporations, among else using it as a base for dealing with Russian market. A great deal of risk capital would be invested into high-tech enterprises. Gambling turnover would equal that of Monaco; entertainment business would flourish unhindered by puritan Scandinavian morals – these opportunities, and being a shopping haven, would bring in a flock of tourists all year round. According to Muldia’s vision, thanks to Naissaar, by 1997 Estonia would have a positive state budget and an excellent international image. Tellingly, the article was illustrated with an image depicting an illuminated night view of Manhattan, the quintessential capitalist highrise city.

The proposition was audacious but not fruitless – the ideas reached top politicians. In October 1994, Estonian government formed a special committee to assess the idea of establishing a special economic zone.[36] There were two locations under discussion – in addition to Naissaar a possibility of making use of a submarine fueling platform in the Gulf of Tallinn as a base for building up an artificial island was considered.[37] The committee, consisting of some top businessmen and an ex-minister of economic affairs, engaged a consultant from the United Kingdom, sir David O’Grady Roche, who within a couple of months presented a report on possibilities of free trade zone in Estonia.[38] He firstly assessed the possibility of turning the whole country into a free trade enclave, pointing out that the young state lacks all four commonly necessary prerequisites for a successful tax free region, namely a stable government, good infrastructure, good general command of English, and pleasant climate. Furthermore, its current parliamentary governing system would be a great hindrance – any benefits offered may be decided against by the next government. Also, the European Union that the country aimed to join – discussions concerning Estonia’s possible entering into the European Union had started already in autumn of 1993, with an association contract agreed later the same year – was strongly against such free trade zones, requiring, quite the contrary, evening out legislation of the member states, and working against possibilities of tax avoidance and money laundering.

The solution O’Grady Roche offered was to create a completely new jurisdiction with a new name, proposing Livonia.[39] It would be a souvereign dependent territory legally modelled after Gibraltar or the Isle of Man. As Naissaar, as the new zone Livonia, would not have any citizens – indeed, initially no inhabitants at all – it would have no one to answer to, ensuring stability of governing. Ireland’s Shannon Scheme, the world’s first free trade zone next to Shannon Airport from 1959, and Customs House Dock in Dubllin were described as models established prior to Ireland joining the European Union – an impetus to organize Livonia as quickly as possible to be able to settle in before the Brussels laws would come to interfere. The constitution of Livonia should be modelled on British charter companies, with a governor and an advisory board. As a sign of stability and trustability the governor was supposed to come from outside of Estonia, and bizarrely, the position was to be inheritable – after all, the vision was drafted by a Britsih baronet. The advisory board was designed to be international with representatives of Estonia, Scandinavian countries and Russia. However, O’Grady Roche was not overly optimistic of physically building up a whole new city on the tabula rasa of Naissaar – creating necessary infrastructure and communications would have required too much investment for a start. Instead, he advocated a solution taken in Dublin Docklands where multinational corporations were actually allowed to pursue their activities first in the whole Dublin, under the licence of the free trading zone, if they insisted they had ‘intentions’ to start operating and building in the actual zone. What would be the benefit and attraction of this separate ‘kingdom’ for Estonians? O’Grady Roche thought the island would be an interesting tourist destination open for everybody as a nature park, or perhaps rather a theme park, with Soviet army railroads converted for joyrides around the island, and Livonia’s own peculiar stamps (not unlike those of Vatican) and currency as a souvenir.

The beginning of 1990s when visions of Naissaar free trade zone were discussed, was a period of proliferation of various similar extraterritorial zones. Actually, the first wave of exponential growth of zones was already in 1970s when such entities were propagated by the United Nations Industrial Development Organization as a legal and economic instrument most suitable for jump-starting economies in developing countries. The benefits offered to companies registered in a zone varied from place to place but might include holidays from income or sales taxes, dedicated utilities like electricity or broadband, deregulation of labour laws, prohibition of labor unions and strikes, deregulation of environmental laws, streamlined customs and access to cheap imported or domestic labour, cheap land and foreign ownership of property, exemption of import/export duties, foreign language services, or relaxed licencing requirements.[40] Generally this meant that in individual deals the zone authority had the power to bypass any law; and in most countries the investors could not be sued in ordinary domestic courts. This created the conditions for a quick spread of zones over the globe: in 1975 there were 79 such entities, employing 800 000 people; in ten years the numbers had doubled; and since the 1990s a new rise was underway, reaching 3500 zones in the world by 2006, employing 66 million.[41]

But already in 1980 the United Nations began to express caution regarding using the zones as anything other than a temporary catalyst. A report marked that the resources redirected to the zones could have rather been used for improving infrastructure, business platforms and other potential relationships with foreign interests withing the regular territory of the state.[42] The main danger in the zones was that instead of acting as a catalyst, it tended to reinforce itself, remaining a flourishing but closed enclave serving only interests of its own. By the beginning of the 1990s, the zone model had begun to mutate, growing into hybrid entities where the original free trade zone merged with container ports, tourist areas, research parks or IT campuses, knowledge villages, and even universities and museums. The focus, initially on trade, had evolved firstly towards manufacturing, and by the 1990s, also towards service and science. At the same time, zones, initially quite utilitarian in their spatial solutions, began to grow more and more into proper urban entities. A new peaking period of the zones in the 1990s and owards was also characterised by aggregation of zones cross-nationally, to circulate products between jurisdictions and employing complex supply chains. The zones formed a network of their own, run by the interests of multinational corporations, quite unhindered by the regulations of traditional states. The zone had become the quintessential locus of globalised neoliberal capitalism, employing a politics of its own – a politics relying on the state of exception inside the borders, and stressing its unpolitical position towards everything outside it.

The period when the future of Naissaar was envisioned both by Tõnis Vint and by David O’Grady Roche was exactly the time when the zone model was undergoing transformation. This is reflected in their different approaches to the issue as well. O’Grady Roche dwelled on the original idea of special economic zone as primarily a juridical entity, focused on alleviated conditions of international trade, whereas the vision of Tõnis Vint more readily correlates with the new developments in the zone model, viewing it as a hybridized entity where economic interests have diversified and allied with tourism, research, and recreation, in the process of becoming an independent urban assembly quite loose from its mother national state. Vint’s view of economic development integrated with and boosted by institutions and activities in the speheres of culture and research also correlates with the ideology of arts as industry, increasingly propagated from the second half of the 1980s onwards, with the concept of creative industries entering public policies internationally in the 1990s.[43]

On the governmental level, the idea as proposed by O’Grady Roche was dropped with the change of cabinet in spring 1995.[44] Tõnis Vint’s vision, however was engaged into a detailed planning process that was initiated after the government had declared the area a nature reserve in March 1995.[45] As a pilot project, the detailed planning process of Naissaar included for the first time an environmental impact assessment, encouraged and financed by the Finnish Ministry of Environment as a structural aid measure for helping to build up democratic planning processes in the newly independent Estonia, effectively making the planning of Naissaar a demonstration project.[46] This entailed initiating a participatory planning process where all parties who had ever expressed interests or generated ideas concerning Naissaar, were invited to planning meetings at the Viimsi county, official commissioner of the planning. By the spring of 1995 when the planning meetings began, there were no spokespersons for the free trading zone from the business circles attending but Tõnis Vint did continue to pursue his visions there as well, taking part of the meetings together with some of his architecture student disciples. The protocols of the planning process testify that his vision, now named “Project East-West” but contentwise exactly copying the text of his most recent article in Eesti Ekspress, was discussed on equal grounds with the other future scenarios, and was included as one in three proposals in the final environmetal impact assessment.[47] A SWOT analysis lists his idea of developing an ideal society as a strength together with a scientifically-based planning, tax-free zone, and international environmental research centre; while threats listed include foreign rule and money laundering.[48] As a separate proposal the planning documentation includes a vision for Naissaar urban park written by a grouping “Etteaim”, consisting of Vint’s disciples and recent architecture graduates Markus Kaasik, Ülar Mark, Andres Ojari, Ralf Tamm, and Ilmar Valdur. In broad terms, their proposal builds on Vint’s one, repeating the lure of international megaproject and high-rise settlements but without a mention of esoteric-universal reasoning. Rather it is more focused on information technology as a necessary future developmental trend for Estonia’s competitiveness, and calls for the universities of Tartu and Tallinn to lead the endeavour, and set up an international ideas competition.[49] The documentation of the lengthy planning process makes it clear that Viimsi county officials justified dropping the ideas of the proposal with practical reasoning: a settlement for estimated 10 000 inhabitants and lively international traffic would have presented huge infrastructural problems and investment needs for an island that lacked any electricity, public water supply and sewerage, or proper harbour. However, it was stressed that the issue never was the utopian character of Vint’s proposal per se but the lack of credible investors to back him up; although in the words of Kaur Lass, the architect responsible for drawing up the detailed planning project, the reluctance of Vint and his disciples to propose even schematic solutions for those infrastructural issues was definitely not helping either.[50]

The situation concerning the detailed planning process and Tõnis Vint’s involvement in it may be characterised by conflicting conceptions of public sphere. The inititators and executives of the detailed planning, with the moral and financial backing of more experienced Finnish colleagues, were aiming at introducing a democratic consensual process, a rational deliberation of a public matter in Habermasian sense where all discussants need firstly to be recognized as legitimate and concerned parties in the matter, and a public and disinterested discussion will lead to a consensus serving the common good.[51] Surely, the common good as well as consensus itself is rather a conceptual ideal based on multiple exclusions as demonstrated by the many critics of the model[52] and challenged by theorists of antagonistic public sphere and democracy.[53] In this context, Tõnis Vint’s entering the process from an illegitimate position in Habermasian sense, as not having a relevant and mutually authorized interest in the matters, with a vision that negates the obvious practical shortcomings of the day and brings the discussion to a whole different level of utopian thought, refusing to ‘normalize’ his proposal with relevant infrastructural proposals that would bring it to a level of comparability with the other ideas on the table, can be read as displaying a contrasting, antagonistic conception of the workings of the public sphere. It is not possible to arrive at a consensical outcome rationally deliberating Vint’s vision and the ideas and hopes of environmentalists and descendants of former landowners; and Vint’s intervention mainly serves the role of keeping the antagonisms on surface, opening up a discussion about possible scope of future plans and aims not only for that particular island but for the country and society as a whole. His role as an agent in the public discussion of the matter, and in the public planning process is to keep open the potential of radical democracy. In this sense, Vint is consistent with his avant-garde artistic position as it was formed in the Late Soviet context, offering a disruptive challenge to the workings of the dominant sphere. But the actual content of his proposal has more dimensions and may at the same time be read as challenging this role internally, rendering his position far more ambiguous.

‘Cosmic energy’ for urban acupuncture

The issues of architectural form or actual methods and ways of establising a future community to Naissaar were allegedly of secondary importance to Tõnis Vint. The free trade zone was to be just a means for a greater end – namely, a spritual transformation of the island itself, Tallinn, the whole Estonian society, and even Western civilization. Throughout his career, Vint has researched and integrated a wide array of intellectual, mental and spiritual impulses – information that he has shared among his disciples as well as in written articles that he was able to publish already during the Soviet times, although a part of it was occasionally also censored for their content.[54] The symbolic content of his art practice has also been meticulously researched[55] but it has not yet been studied in the context of New Age into which the ideological background of his work at least partially falls. In Vint’s case, the assembly and making use of different Eastern philosophical systems and spiritual practices like tantra, hinduism, taoism and others, and their mixing with Western neo-pagan references as well as symbolism and pop art is not really justifiable as postmodern juggling – it has widely been accepted that his approach always lacked the postmodern irony.[56] Although Vint has said that his initial drive towards Eastern inspirations was visual, nurtured in the art museums of Moscow and St Petersburg in the 1960s, and only from that ground the philosophical inquiries followed[57], the resulting intellectual system that he gradually built up bears strong semblance to New Age culture, not the least in its desire to establish an alternative mental sphere that in the West had strong adherence to the whole counter-culture of the 1960s. In the Soviet context, these kind of activities had even stronger counter-cultural connotations, with Eastern spiritual practices seen as among one of the means of establishing an alternative reality[58], the practitioners effectively contributing to a subculture.[59] The subculture Vint created in the 1960s-1970s was based on living on one’s own principles, and has been interpreted as detaching himself of the surrounding Soviet realities as much as possible.[60] Whenever he wrote of the future then, he avoided concretising, where and within which boundaries the processes that interested him could function.[61] An interest in spiritual aspects of world cultures helped to build up and reinforce a life-world of his own rules, existing mentally separate from the surrounding Soviet realities – a private aesthetic universe as it has been called.[62]

With the arrival of the newly independent republic and the new social rules, Vint found himself ready to enter public discussion but the intellectual and spiritual worldview he presented fell into a context that had greatly transformed itself as well. In the West, the latter half of the 1980s had seen a transformation of the New Age, now with much greater internal diversity and a proliferation of new movements that were aligning itself with the ethos of capitalist modernity and had an increasing appeal to the prevailing yuppie mentality. Earlier rhetoric of ‘authenticity’, ‘harmony’, ‘tranquility’, and ‘creativity’ were increasingly substituted for value-language of ‘power’, ‘energy’, and ‘abundance’, and New Age became increasingly to be treated as a utilitarian resource for catering for personal ends of stimulation, pleasure, and affluence.[63] The hedonistic lifestyle of desire and mass consumption increasingly associated with spiritual practices has even prompted seeing tantrism as definitive for late capitalism in the way protestantism was for early capitalism.[64] In the post-Soviet context, perestroika meant the end of decades-long imposed atheism and whereas in many post-Soviet countries this primarily meant reinstatement of traditional churches merged with nationalistic tendencies, there was also a surge in interest in different manifestations of New Age – a specific situation that has been called a ‘postatheist minimal religiosity’ aiming towards holistic spirituality independent of traditional liturgies.[65] Instead of supporting resistant or alternative lifestyle as in the late Soviet times, New Age ideas made their way big into popular culture, mainly by way of published books and articles in written media.[66] Thus the publication of Vint’s articles about geomantic analysis of Tallinn and the accumulators of cosmic energy in Naissaar in major newspapers like Eesti Ekspress fell into a context of the same mainstream media outlets frequently publishing New Age related features from astrology, numerology and esoteric healing practices to UFO-spotting. This definitely affected the reception of his ideas although the relationship is by no means unambiguous – at the same time, the intense popular interest towards all previously unheard of exotic practices, and an open willingness to discuss such matters on nonjudgemental basis, in a way also lowered the threshold of entering into discussion of the issue presented in such a way. The general popular rise of interest towards New Age as a backdrop worked both ways - it was easier to publicly present a case like Vint’s geomantic proposal and get it seriously debated but equally easier to lump it together with other mumbo-jumbo and dismiss it as such.

However, in order to disentangle the position and effect of Vint’s Naissaar project under the particular social circumstances, it is important to take into consideration the ideological implications of its New Age dressing. Whereas the first wave, countercultural New Age included an element of rebellion against modernity, Vint’s proposal for Naissaar with its high-tech enterprises housed in high-rises is certainly something else, adhering more to the yuppie-friendly 1980s version of the phenomenon. The all-too-natural amalgamation of New Age sensibilities and neoliberalist capitalism has been pointed out by Slavoj Žižek, employing a term ‘Eurotaoism’, initlially forged by Peter Sloterdijk.[67] Žižek maintains that New Age, blending Eastern spiritual practices of very different sources, contributes to extreme individualism in a way easily taken advantage of by our current neoliberal capitalism. Claiming one’s full responsibility for all apsects of life, New Age cultivates passivity towards rapid social changes, an inclination for drifting along whereas maintaining an inner distance and indifference, wilfully blinding oneself towards more structural agents like overall capitalist dynamics and market forces of laissez-faire economies. At the same time, such mental disposition enables one to fully participate in the late capitalist frenzy, maintaining a belief that we are not fully immersed in it but actually seeing the worthlessness of this spectacle and able to withdraw to the cultivation of the inner self or aiming at some higher ends independent of it.[68] This is exactly the disposition detected in Vint’s Naissaar project as well, having no difficulty in presenting possibly exploitative free trade zone economy and morally dubious entertainment industries and unrestricted gambling paradoxically as ultimately serving a higher end of spiritual transformation. His liberal capitalist sympathies are unhindered when he calls the environmentalists’ concerns for nature ‘extreme leftism’, ‘a rebirth of French maoism’, and an overall obstruction of civilisation; in a similar vein, he condemns the preservationists’ concern for Kalamaja as nurturing a crime hub, and proposes to start implementing the vision by starting building first high-rises on Kopli peninsula on mainland Tallinn.[69] At the same time, Vint’s New Age rhetoric implies universality in a way that renders his vision somehow unquestionable, somehow definitive, using an expression ‘building up a centuries-old architectural utopia’[70] as if the idea of utopia would be something definitive and could never have taken different manifestations. This gives his futuristic vision an odd claim for historical legitimation that adds its own twist to the whole restaurative ethos of the newly reestablished republic.[71] Also, the New Age undertones of Vint’s project hint at a surprisingly socially conservative traditionalist stance regarding gender – admitting that the buildings on his drawings have always been conceptualised as representing a male or a female element[72], Vint has claimed that the buildings on Naissaar must be high and phallic to be able to impregnate the female island for a new culture to be born.[73]

Conclusion

Having examined Tõnis Vint’s Naissaar vision from diverse viewpoints like its integrity with the artist’s earlier work, the proposal’s correlation with global developments in free trade zone policies as well as the ideological implications of its New Age rhetoric under the changing social conditions of the era, the project emerges as a peculiar example of the transition or interregnum era culture. On the one hand it testifies of a continuation of ideas developed during the Late Soviet era; on the other hand it shows the scope of changes in social circumstances with a radically widened public arena available for entering from a seemingly most outrageous position. The project highlights the lack of taboos during this period of formation of a public sphere, and a look at the unfolding of the detailed planning process over a couple of years shows the initial openness with inviting antagonistic interventions such as Vint’s proposal, as well as its workings toward a more normalised, consensus-oriented understanding of the planning process. The project, encompassing considerations as diverse as realpolitical economic gain as well as spirituality and mysticism, could be read as characteristic of the society in the making, open and willing to give serious consideration to any kind of ideas, lacking conventional protocols that would keep the issues within their separate confines. Yet examining the project in a wider context of global developments renders it as liberal-conservative in a way the artist was not yet able to see himself. On the one hand, the marrying of the futuristic vision with extremely liberal opportunistic economic scheme may be seen as socially irresponsible, riding the tide of the very first years of the newly independent republic, unable to maintain a critical distance from mainstream rhetoric. On the other hand, the New Age spirituality, the way it presented itself, reinforced even more the new extremely liberal social mentality that had come to replace communal vibes of the national awakening of the 1980s, contributing to a gradual closing of the radical openness of the transition moment. The vision of Tõnis Vint is utterly characteristic of the incoherence of the time, the artist trying to retain and pursue his avant-garde cause of the previous era but yet too innocent in regard to the new era for it to work out.

[1]See, e.g Caroline Humphrey, Does the Category ‘Postsocialist’ Still Make Sense? – C. M. Hann (ed), Postsocialism: Ideals, Ideologies and Practices in Eurasia. London and New York: Routledge, 2002, pp 12–15; Zsuzsa Gille, Is There a Global Postsocialist Condition? – Global Society, 24 (2010), pp 9 – 30; Alison Stenning, Kathrin Hörschelmann, History, Geography and Difference in the Post-Socialist World: Or, Do We Still Need Post-Socialism? – Antipode, Vol 40, issue 2, March 2008, pp 312–335; Mariusz Czepczynski, Cultural Landscapes of Post-Socialist Cities: Representation of Powers and Needs. London: Routledge, 2008.

[2]Alison Stenning, Kathrin Hörschelmann.

[3]Andrew C. Janos. From Eastern Empire to Western Hegemony: East Central Europe Under Two International Regimes. - East European Politics and Societies Vol 15(2), 2001, pp 221–249.

[4]Alison Stenning, Kathrin Hörschelmann.

[5]Marju Lauristin, Peeter Vihalemm. The Political Agenda During Different Periods of Estonian Transformation. – Journal of Baltic Studies 1, 2009, pp 1–28.

[6]Andrew Arato. Lefort, Philosopher of 1989. - Constellations, Vol 19, No 1 (2012), pp 23–9.

[7]Hasso Krull. Ükssarvede lahkumine [The Departure of Unicorns]. – Eesti Ekspress, December 30, 1994. Cultural commentator Anders Härm has also claimed that Estonia was democratic only in 1988 – 91/92, see Anders Härm, Eesti oligarhia, in Eesti Päevaleht, November 30, 2012.

[8]Malcolm Miles. Public spheres. – Angela Harutyunyan, Kathrin Hörschelmann, Malcolm Miles. Public Spheres After Socialism. Bristol and Chicago: Intellect, 2009, pp 133–150.

[9]Piotr Piotrowski. Art and Democracy in Post-Communist Europe. London: Reaktion Books, 2012. Introduction: Agoraphilia After Communism, pp 7–14.

[10]For a more comprehensive overeview of conceptual and unrealised urban and architectural projects of the era, see Ingrid Ruudi, Ehitamata. Visioonid uuest ühiskonnast 1986 – 1994. Unbuilt. Visions for a New Society, 1986 – 1994. Tallinn: Eesti Arhitektuurimuuseum, 2015.

[11]Tõnis Vint. Naissaar – tulevikuvisioon [Naissaar – A Vision for the Future]. Ehituskunst 11/1995, 4–10.

[12]Tõnis Vint. Kas Naissaar suudaks päästa Eesti tippteaduse ja kõrgkultuuri? [Would Naissaar be able to save Estonian top science and high culture?]– Eesti Ekspress 16.04.1993; Tõnis Vint. Naissaar. Kaks teed tulevikku [Naissaar. Two paths towards the future]. – Eesti Ekspress 12.01.1995.

[13]Tõnis Vint. Naissaar ja Tallinna geomantiline selgroog [Naissaar and the geomantic spine of Tallinn]. – Elu Pilt 4, 1993.

[14]The beginning of 1990s saw Vint engaging in another large-scale urban vision. The ideas of geomantics and urban acupuncture developed in Naissaar project were also connected to a proposition concerning restructuring of Tallinn coastal area and redesigning the Russalka monument by Amandus Adamson from 1902, to cleanse the city of landmarks otherwise making up a ‘death arch’ on the coast; the same proposition praised the speculative idea to establish a World Trade Center to central Tallinn in the form of a high-rise of at least 60 floors. See Tõnis Vint. Suur vabanemine surmakaarest [The great riddance from the death arc]. – Hommikuleht 29.10.1994; Tõnis Vint. Mustast surmainglist kuldseks päikseingliks [From the black angel of death into a golden angel of sun]. – Eesti Ekspress 21.10.1994. His interest in issues of spatial organization and symbolism continued with an entry for independence memorial competition in 2001 that was awarded a purchase prize; see Vabaduse väljak. Vabadussammas. Kolm õnneväravat [Independence Square. Independence Statue. Three Gates of Happiness]. www.stuudio22.ee/node/3.

[15]Osoon. Elu võimalikkusest Naissaarel. ETV 10.01.1994, https://arhiiv.err.ee/vaata/osoon-elu-voimalikkusest-naissaarel

[16]Tuleviku linn [The city of the future]. Directed by Mariina Mälk. ETV 1995.

[17]The exhibition “Tornid ja väravad” [Towers and gates] took place at the Estonian National Library in September 10th – September 27th, 1996.

[18]Two years later, another article “Naissaar – kaks teed tulevikku” (Eesti Ekspress 12.01.1995) used the same image without added national flags, plus Chernikhov’s Composition No 18 (1929), to illustrate two settlements at the Northern and Southern ends of the island. In both cases, Chernikhov’s autorship of the images went uncredited, but in conversations Vint has never denied him being an inspiration for the project.

[19]Tõnis Vint. Naissaar ja Tallinna geomantiline selgroog.

[20]Ibid.

[21]Vint. Naissaar. Kaks teed tulevikku.

[22]Naissaar. Project. S.l, s.d, unpaginated. Archive of Tõnis Vint.

[23]Conversation with Ralf Tamm, Tõnis Vint’s main assistant in the project, March 24th, 2016.

[24]Tõnis Vint in TV broadcast “Tuleviku linn” (City of the Future), 1995.

[25]Tõnis Vint. Naissaar ja Tallinna geomantiline selgroog.

[26]Elnara Taidre. Graafilisest kujundist keskkonnakavanditeni. Tõnis Vindi esteetilisest utoopiast [From graphic image to environmental design. About the aesthetic utopia of Tõnis Vint]. – Sven Vabar, Jaak Tomberg, Mari Laaniste (eds). Etüüde nüüdiskultuurist 4. Katsed nimetada saart. Artikleid fantastikast. Tartu: Tartu Ülikooli kirjastus, 2013, pp 49–67.

[27]Vint. Naissaar. Kaks teed tulevikku.

[28]ibid.

[29]Elnara Taidre. Graafilisest kujundist keskkonnakavanditeni.

[30]See Sgrid Rausing. History, memory and identity in post-Soviet Estonia: the end of a collective farm. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004, pp 44-45.

[31]Vint. Naissaar. Tulevikuvisioon. – Ehituskunst 11/1995, pp 4-10.

[32]Osoon.

[33]Reinhold Martin has caimed that an island or a closed enclave is one of the most central configurations of postmodern space, see Reinhold Martin. Utopia’s Ghost. Architecture and Postmodernism, Again. University of Minnesota Press, 2010, chapter Territory. From the Inside, Out, pp 1–26.

[34]Vint. Naissaar. Kaks teed tulevikku.

[35]Sulo Muldia. Pilvelõhkujad Naissaarel. Rikas Eesti kuus aastat hiljem [High-rises on Naissaar. Rich Estonia in six years]. – Eesti Ekspress 19.01.1990.

[36]Kalle Muuli. Naissaare superprojekt [Naissaar superproject]. – Rahva Hääl, 21.01.1995.

[37]Conversation with Jaak Leimann, member of the committee, 27.05.2016.

[38]Plaan maksuvaba piirkonna asutamiseks Tallinnas [A plan for establishing a tax-free zone in Tallinn]. – Rahva Hääl, 23.01.1995.

[39]It remains a pure speculation if O’Grady Roche got inspration for the name from Tõnis Vint’s concept of Celtic Livonia, or if they ever discussed the matter.

[40]Keller Easterling. Extrastatecraft. The Power of Infrastructure Space. London: Verso 2014, p 34.

[41]Thomas Farole, Gokhan Akinci. Introduction. – Thomas Farole, Gokhan Akinci (eds). Special Economic Zones. Progress, Emerging Challenges, and Future Directions. Washington: The World Bank, 2011, pp 1–21.

[42]Keller Easterling, Extrastatecraft, p 34.

[43]Susan Galloway, Stewart Dunlop, A Critique of Definitions of the Cultural and Creative Industries in Public Policy. – International Journal of Cultural Policy, Vol 13, No 1, 2007, p 17.

[44]Conversation with Jaak Leimann, 27.05.2016.

[45]Naissaare looduspargi moodustamine ja kaitse-eeskirja kinnitamine [Establishment of Naissaar nature reserve and endorsement of its protection regulations]. – Riigi Teataja 1/1995.

[46]Conversation with Kaur Lass, main architect of Naissaar detailed planning project at ENTEC OÜ in 1995 – 1997, 29.01.2016.

[47]Naissaar. Work No 59/95, ENTEC OÜ archive.

[48]Ibid.

[49]Ibid.

[50]Conversation with Kaur Lass.

[51]See Jürgen Habermas. The Structural Trasformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society. Cambridge: Polity 1989 [1962].

[52]See Nancy Fraser. Rethinking the Public Sphere. A Contribution to the Critique of Actually Existing Democracy. – Social Text 25/26 1990, pp 56–80.

[53]Chantal Mouffe. Democracy, Power and the ‘Political’. – Chantal Mouffe. The Democratic Paradox. London: Verso, 2000, pp 17-35.

[54]For instance, Tõnis Vint. Kuldne lill. Tantra. Tao. [Golden flower. Tantra. Tao] – Kunst 2/75, a magazine issue that was destroyed as the whole printrun.

[55]See Elnara Taidre. Tõnis Vindi kunstipraktikad kui sünkretistlik tervikkunstiteos. Tõnis Vint’s art practices as a syncretistic total work of art. – Elnara Taidre (ed). Tõnis Vint ja tema esteetiline universum. Tõnis Vint and his aesthetic universe. Tallinn: Eesti Kunstimuuseum, 2012, pp 19–40.

[56]Elnara Taidre. Eesti kunsti viimane modernist ja esimene postmodernist. Intervjuu Tõnis Vindiga. [The last modernist and the first postmodernist of Estonian art: Interview with Tõnis Vint] – Sirp 31.05.2012.

[57]Tõnis Vint. Algimpulsid. [Initial impulses] – Ehituskunst 33-34/2002, p 40.

[58]See Maria Popova. Underground Hindu and Buddhist-inspired religious movements in Soviet Russia. – Usuteaduslik Ajakiri 1/2013, pp 99–115.

[59]See also, Alexei Yurchak. Everything Was Forever, Until It Was No More. The Last Soviet Generation. Princeton University Press, 2006, chapter Deterritorialised Milieus, esp. p. 154.

[60]However, this was never a complete withdrawal – the way Vint advocated for his aesthetic choices in magazines with all-Soviet circulation, including presentations of his own apartment interiors both in Soviet Estonian magazine Kunst ja Kodu as well as in Finnish Kodin Kuvalehti, indeed testify of his intention (and success) to have a wider social impact, see Andres Kurg, Empty White Space: Home as a Total Work of Art during the Late-Socviet Period, in Interiors. Design, Architecture, Culture, vol 2 (I), 2011, pp 45–68.

[61]Sirje Helme. Korter nr 22 – üks Tõnis Vindi esteetilise universumi planeetidest. Flat No 22 – a Planet in Tõnis Vint’s Aesthetic Universe. – Elnara Taidre (ed). Tõnis Vint ja tema esteetiline universum. Tõnis Vint and his aesthetic universe. Tallinn: Eesti Kunstimuuseum, 2012, pp 46.

[62]Elnara Taidre. Tõnis Vindi kunstipraktikad.

[63]Paul Heelas. The New Age: Values and Modern Times. – Lieteke van Vucht Tijssen, Jan Berting, Frank Lechner (eds.) The Search for Fundamentals. The Process of Modernisation and the Quest for Meaning. Dordrecht: Springer, 1995, pp. 143–171.

[64]Hugh B Urban. The Cult of Ecstacy: Tantrism, the New Age, and the Spiritual Logic of Late Capitalism. - History of Religions, Vol. 39, No. 3 (Feb., 2000), pp. 268-304.

[65]Mikhail Epstein. Post-Atheism. From Apophatic Theology to Minimal Religion. – Mikhail Epstein, Alexander Genis, Slobodanka Vladiv-Glover (eds.) Russian Postmodernism. New Perspectives on Post-Soviet Culture. New York, Oxford: Berghahn Books, 1999, pp. 345-393.

[66]Marko Uibu, Marju Saluste. Lugejate virtuaalne kogukond: Kirjandus ja ajakirjandus vaimsete-esoteeriliste ideede kandja ja levitajana [A Virtual Community of Readers: Literature and journalism as carriers and distributors of spiritual and esoteric ideas]. – Marko Uibu (toim). Mitut usku Eesti 3: Uue vaimsuse eri. Tartu: Tartu Ülikooli kirjastus, 2013, pp 79 – 106.

[67]Peter Sloterdijk. Eurotaoismus. Zur Kritik der politischen Kinetik. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 1989.

[68]Slavoj Žižek. On Belief. London: Routledge, 2001, pp 12–15.

[69]Tõnis Vint. Kaks teed tulevikku.

[70]The phrase is used repeatedly in most of Vint’s articles as well as in his project description in the detailed planning documentation.

[71]Due to strong restaurative tendencies and general looking back towards the Republic of Estonia of 1918 – 1939, Marek Tamm has described the reestablished republic as ‘a republic of historians’, see Marek Tamm, „Vikerkaare ajalugu”?: Märkmeid üleminekuaja Eesti ajalookultuurist [‘A Vikerkaar history’? Notes on the Estonian history culture of the transition era] . – Vikerkaar 7/8, 2006, pp. 136–143.

[72]Elnara Taidre. Eesti kunsti viimane modernist ja esimene postmodernist. Intervjuu Tõnis Vindiga.

[73]Tõnis Vint. Naissaar ja Tallinna geomantiline selgroog. – Elu Pilt 4/1993. Naissaar, translating Female island, was first mentioned as Terra Feminarum in 1075.

Add a comment